Today we will teach you how to say school in Korean. You will also learn a variety of words and phrases related to all things school.

Being a student and attending school can be enjoyable as it’s where you can meet a lot of friends. If you’re currently studying in South Korea, these terms might come in handy.

Sit down comfortably with your notes open, and let’s get to studying!

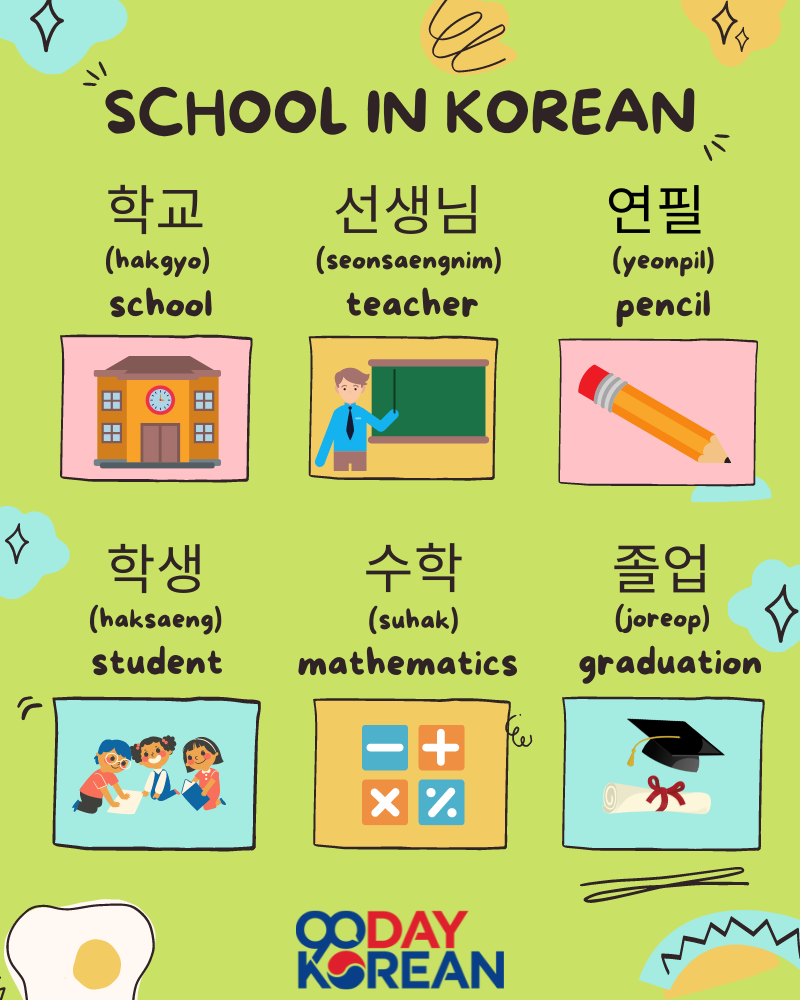

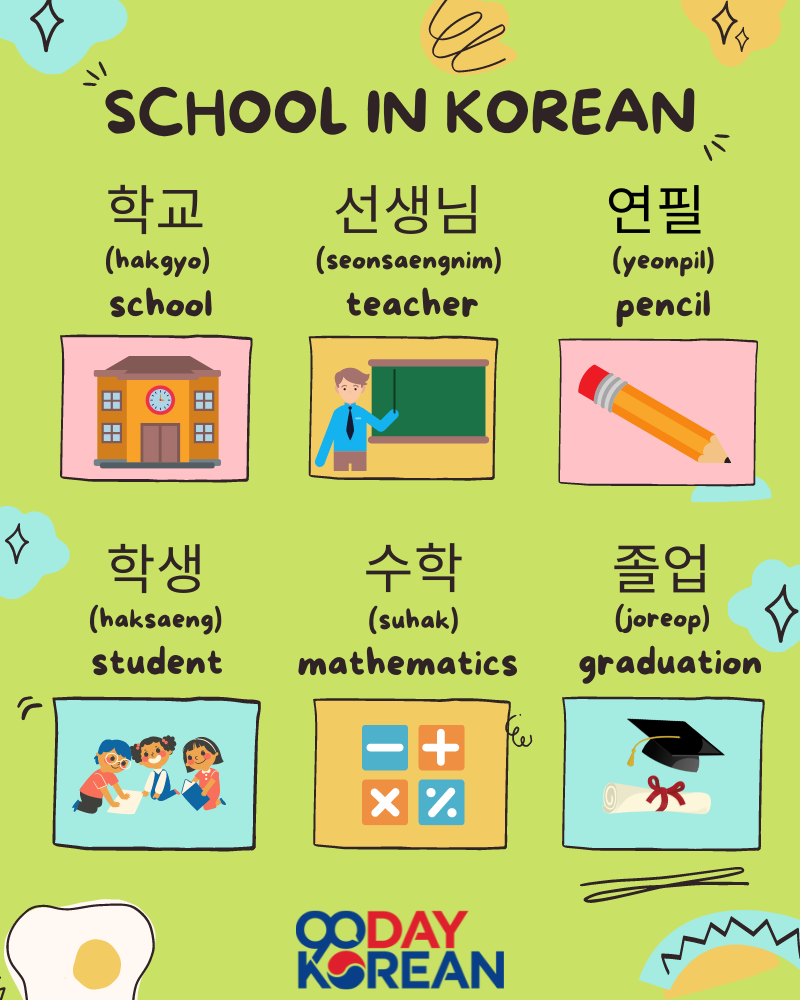

How to say “school” in Korean

You can say “school” in Korean as 학교 (hakgyo). For each different level of schooling, from elementary school to university, the word 학교 is attached.

This lesson will primarily focus on the words related to school in Korean. However, there will be a separate article focusing more on schools in South Korea.

Vocabulary for school in Korean

Here is some common vocabulary related to school in Korean.

Words for schools in South Korea

There are different levels of education in South Korea. Here are some of them.

| Korean | English |

| 초등학교 (chodeunghakgyo) | elementary school |

| 중학교 (junghakgyo) | middle school |

| 고등학교 (godeunghakgyo) | high school |

| 대학교 (daehakgyo) | university |

| 대학원 (daehagwon) | graduate school |

| 학원 (hagwon) | cram school, private academy |

| 유치원 (yuchiwon) | kindergarten |

| 전문대 (jeonmundae) | college |

| 어학원 (eohagwon) | language school |

| 어학당 (eohakdang) | language school |

| 기숙 학교 (gisuk hakgyo) | boarding school |

Words for people related to school in Korean

Here are some words for roles that people have related to school.

| Korean | English |

| 교수 (gyosu) | professor |

| 교사 (gyosa) | school teacher |

| 선생님 (seonsaengnim) | teacher |

| 학생 (haksaeng) | student |

| 중학생 (junghaksaeng) | middle school students |

| 고등학생 (godeunghaksaeng) | high school students |

| 초등학교 선생님 or 초등학교 교사 (chodeunghakgyo seonsaengnim or chodeunghakgyo gyosa) | primary school teacher |

| 반 친구들 (ban chingudeul) | classmates |

Words for subjects in Korean

Different subjects are taught at school. Here are some of them in Korean.

| Korean | English |

| 과목 (gwamok) | subject |

| 수학 (suhak) | mathematics |

| 과학 (gwahak) | science |

Verbs related to school in Korean

Below are some action words related to school in Korean.

| Korean | English |

| 가르치다 (gareuchida) | to teach |

| 배우다 (baeuda) | to learn |

| 연습하다 (yeonseupada) | to practice |

| 공부하다 (gongbuhada) | to study |

| 교육하다 (gyoyukada) | to educate |

Other words related to school in Korean

We’ve also listed down additional essential vocabulary related to school in Korean.

| Korean | English |

| 학부 (hakbu) | department |

| 수업 (sueop) | class |

| 시험 (siheom) | exam |

| 강당 (gangdang) | auditorium, assembly hall |

| 학교식당 (hakgyosikdang) | school cafeteria |

| 교실 (gyosil) | classroom |

| 학년 (hangnyeon) | grade |

| 교육 (gyoyuk) | education |

| 도서관 (doseogwan) | library |

| 학기 (hakgi) | semester |

Elementary school in Korean

Elementary school in Korean is called 초등학교 (chodeunghakgyo). The elementary school falls under primary education.

Middle school in Korean

Falling under secondary education, middle school in Korean is called 중학교 (junghakgyo). Middle school students are called 중학생 (junghaksaeng) in Korean.

High school in Korean

After middle school, the high school level comes next. The word for high school in Korean is 고등학교 (godeunghakgyo). A high school student is called 고등학생 (godeunghaksaeng) in Korean.

Graduate school in Korean

The word for graduate school in Korean is 대학원 (daehagwon).

Graduation in Korean

The word for graduation in Korean is 졸업 (joreop), and the verb “to graduate” is 졸업하다 (joreopada). The word for graduation ceremony is 졸업식 (joreopsik). The word for ceremony is 식 (sik).

University in Korean

The word for university in Korean is 대학교 (daehakgyo). Sometimes, when spoken of a specific university, for example, 한양대학교 (hanyangdaehakgyo), it may get shortened as 대 (dae). In other words, instead of saying the full 한양대학교, you may just say 한양대 (hanyangdae). Like this:

한양대에서 졸업했어요.

(hanyangdaeeseo joreopaesseoyo.)

I graduated from Hanyang University.

College in Korean

The word for college in Korean is 전문대 (jeonmundae). However, frequently the term 대학교 (daehakgyo) is used interchangeably or is shortened as 대학 (daehak). Typically the word 전문대 is used specifically for colleges with programs lasting 2-3 years, as opposed to a university’s 4-year degrees.

Teacher in Korean

There are two words for “teacher” in the Korean language. The first one is 교사 (gyosa) which translates to school teacher, and the other one is 선생님 (seonsaengnim) which literally means teacher. The difference between the two is that 선생님 (seonsaengnim) is an honorific, while 교사 (gyosa) isn’t.

In addressing your teachers directly, you should say 선생님 (seonsaengnim), not 교사 (gyosa).

For example, “Hello, teacher!” in Korean is 선생님, 안녕하세요! (seonsaengnim, annyeonghaseyo!) and not 교사, 안녕하세요! (gyosa, annyeonghaseyo!).

Student in Korean

When there’s a teacher, there’s also a student. And Korean students are generally called 학생 (haksaeng). As you learn Korean and improve your language skills, you can also consider yourself as 학생 (haksaeng).

Book in Korean

The word for book in Korean is 책 (chaek). However, for school book specifically, the words typically used are 교과서 (gyogwaseo) and 학교 도서 (hakgyo doseo).

Study in Korean

There are a few words for how to say study in Korean. Perhaps the most common one is 공부 (gongbu). You can also use it as the verb “to study” by attaching 하다 (hada) to the verb, like this 공부하다 (gongbuhada). Sometimes the word 학습 (hakseup) is also used. More specifically, this noun means “learning.”

Pencil in Korean

The word for pencil in Korean is 연필 (yeonpil). And the word for “pen” in Korean is 펜.

Go to School in Korean

Lastly, you will probably want to know how to say go to school in Korean. The phrase for this is 학교에 다니다 (hakgyoe danida). The word 학교 means “school,” and the verb 다니다 means “to go” and “to attend.” Based on the formality, you can drop 다 and add -녀(요) to use the verb in action.

The 에 attached to 학교 is an integral Korean particle, noting location or time. If you are still unfamiliar with this particle or Korean particles in general, we kindly ask you to refer to our particle guide.

Phrases related to school in Korean

Now that we’ve learned some Korean words related to school in Korean, let’s level it up to the Korean phrases below.

좋은 대학교에 입학하게 되기 위해서 열심히 공부해요. (joeun daehakgyoe ipakage doegi wihaeseo yeolsimhi gongbuhaeyo.)

I study hard because I want to get into a good university.

제가 제일 좋은 수업은 영어에요. (jega jeil joeun sueobeun yeongeoeyo. )

My favorite school subject is English.

지금 한국어학원을 다니고 있어요. (jigeum hangugeohagwoneul danigo isseoyo.)

I am currently attending Korean language school.

일주일에 학원에서 3개 수업을 들어요. (iljuire hagwoneseo 3gae sueobeul deureoyo.)

I take three classes a week in a private academy.

And now you should be ready to talk about school in Korean! Do you have plans to attend school in South Korea, or have you already attended school in Korea? How else can you make today’s material useful to you? Let us know in the comments below!

The post School in Korean – Words and phrases related to education appeared first on 90 Day Korean®.

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Recent comments