Temple History

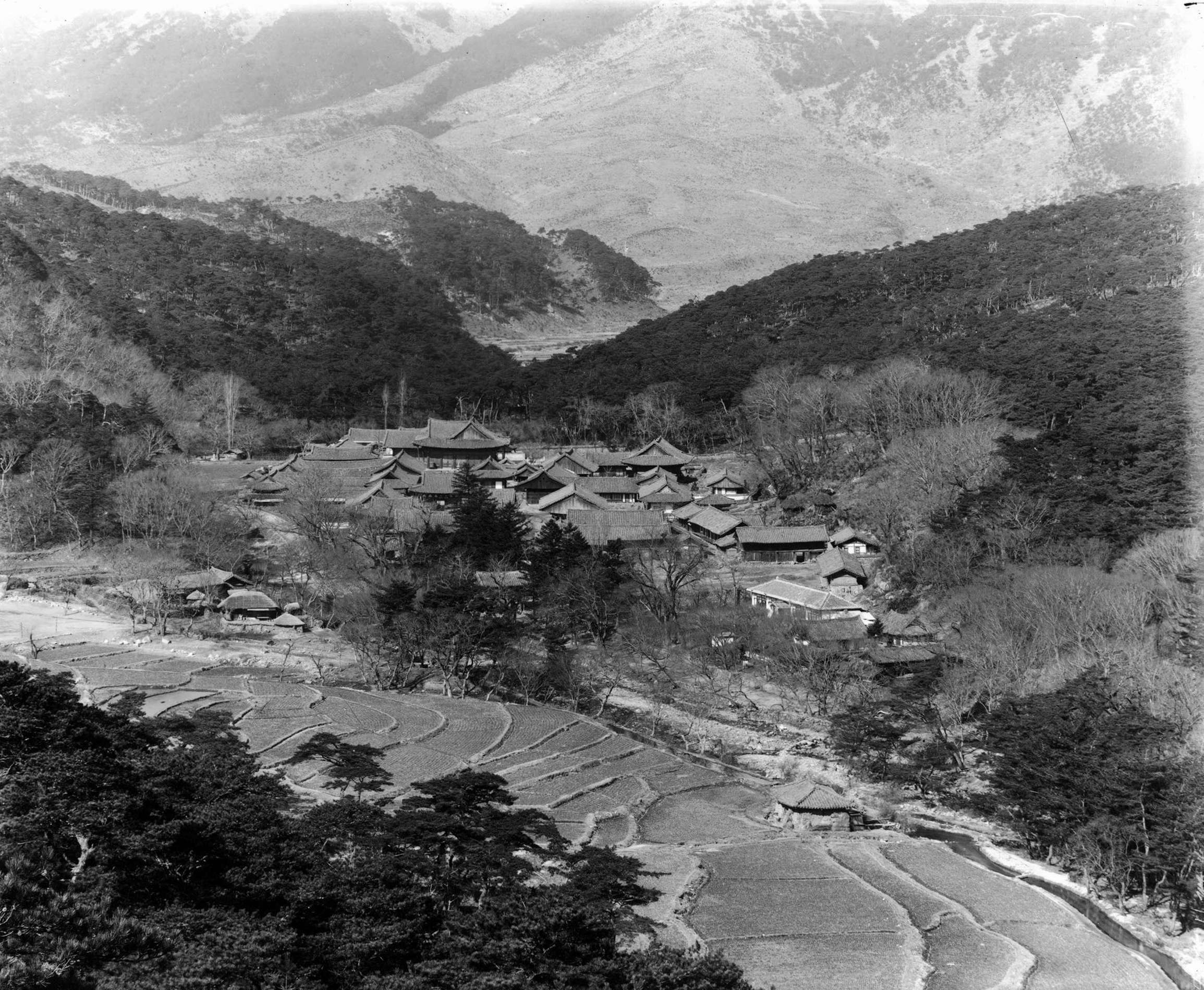

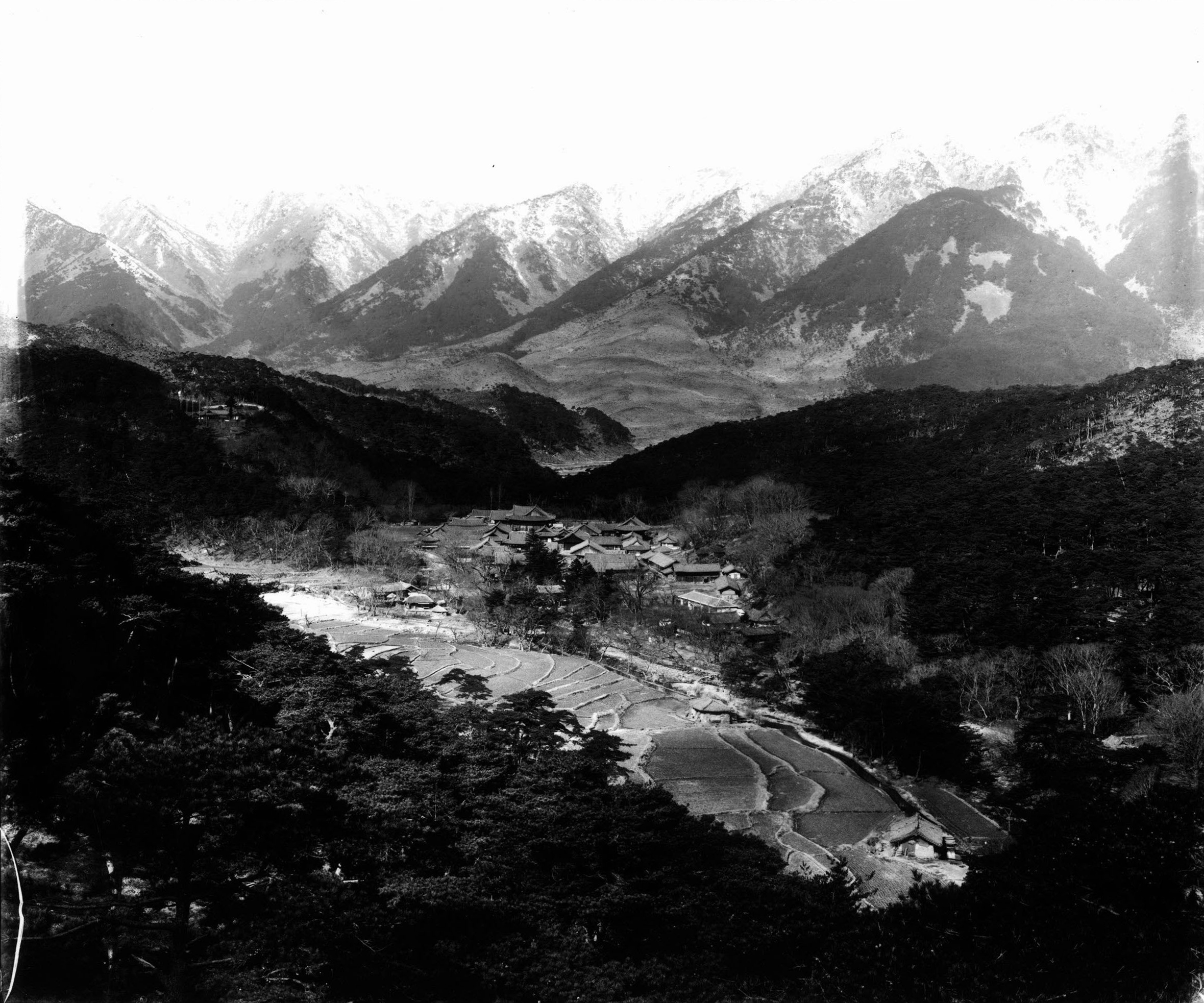

Tongdosa Temple, which is located in northern Yangsan, Gyeongsangnam-do, is the largest temple in all of Korea with nineteen hermitages spread throughout its vast grounds. Tongdosa Temple means “Passing Through to Enlightenment Temple” in English. Tongdosa Temple was first founded in 646 A.D. by the famed monk Jajang-yulsa (590-658 A.D.). According to the “Tongdosa-sarigasa-sajeok-yannok,” the temple site was originally a large pond, but it was covered over by landfill so as to allow for Tongdosa Temple to be built. Also, and according to the “Tongdosa-yakji,” the name of Mt. Yeongchuksan, which is where Tongdosa Temple is located, was named after the mountain in India where the Historical Buddha (Seokgamoni-bul) gave his dharma talks. Mt. Yeongchuksan had the same rocky appearance as the original in India. So using Chinese characters (Hanja), the mountain was called Yeongchuksan.

According to the Samguk Yusa, or Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms in English, Jajang-yulsa founded Tongdosa Temple. Jajang-yulsa traveled to Tang China (618–690, 705–907 A.D.) in 636 A.D. to study alongside ten other monks. Upon his return to the Silla Kingdom (57 B.C. – 935 A.D.), Jajang-yulsa brought with him Buddhist texts and holy relics of the Buddha that were given to him by Munsu-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom) during his travels in Tang China. Besides the Great Tripitaka (a collection of Buddhist sutras, laws, and treatises), Jajang-yulsa also returned to Silla with Seokgamoni-bul’s (The Historic Buddha’s) robe, alms bowl, a tooth, and a part of his jaw bone. Jajang-yulsa acquired all these items in Tang China in 643 A.D. After its establishment, Tongdosa Temple gradually grew in size and became the centre for Korean Buddhism under the protection of the royal family.

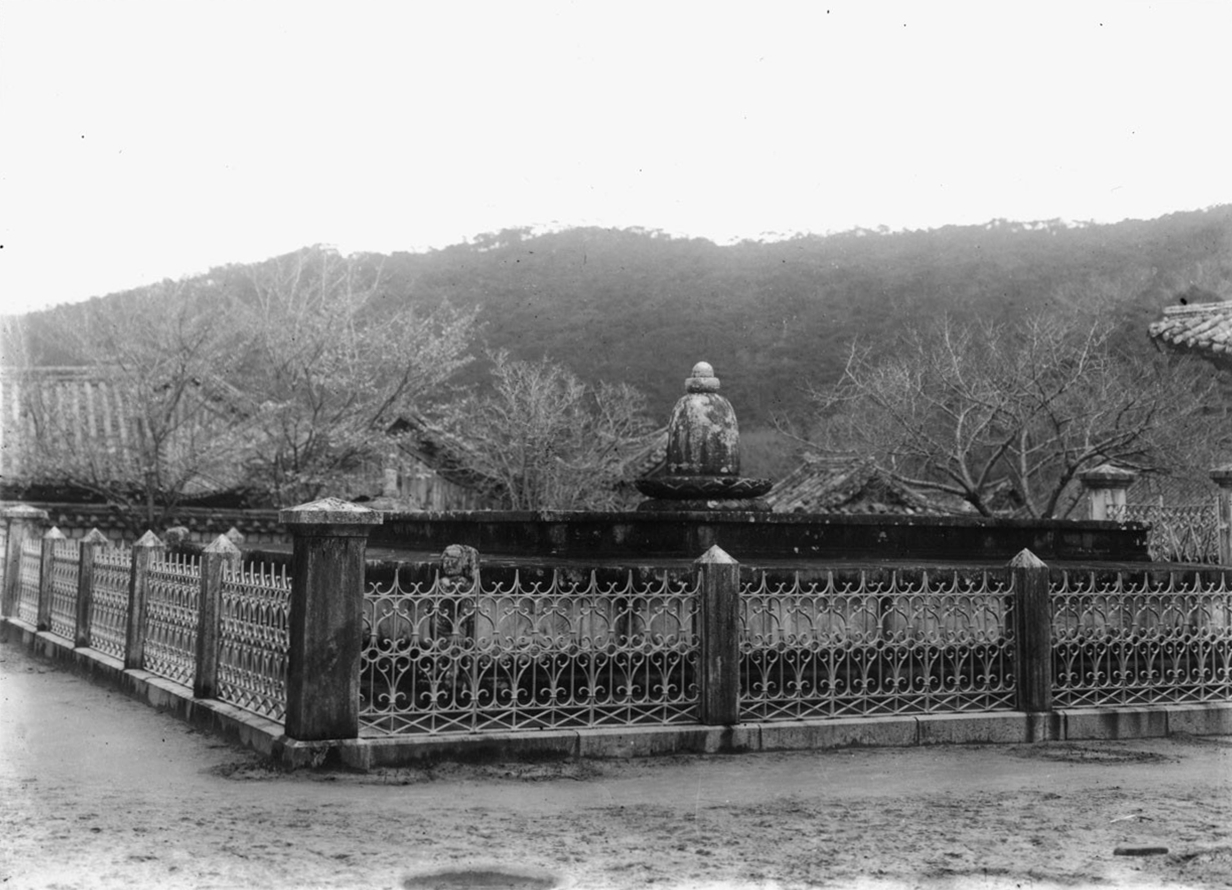

So much of Tongdosa Temple’s history centres on the preservation of the sari (crystallized remains) of Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha). At the time of its founding by Jajang-yulsa, Tongdosa Temple had several buildings that surrounded the centrally located Geumgang-gyedan (The Diamond Altar), which housed the sari of the Buddha. Later, and in 1085, during the reign of King Seonjong of Goryeo (r. 1083-1095), Tongdosa Temple was greatly expanded. According to the Samguk Yusa, again, Commander Kim Ri-saeng and Sirang Yuseok were commanding the troops on the east side of the Nakdong River under the orders of King Gojong of Goryeo (1213-1259) in 1235. Together, they visited Tongdosa Temple, where they lifted the stone lotus bud at the centre of the Geumgang-gyedan, where the sari of the Buddha are housed. They wanted to pay their respects to Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) as devout Buddhists. One of the glass containers inside the stone lotus bud cracked, so Yuseok donated a crystal container he had to help store some of the sari. According to the Samguk Yusa, this was the first time that human hands touched the Buddha’s sari at Tongdosa Temple.

Several other buildings at Tongdosa Temple were built in 1340 and 1369 like the Myeongbu-jeon Hall, the Geukrak-jeon Hall, the Yaksa-jeon Hall, and the Hwaeom-jeon Hall. Then in 1377, when the Japanese trespassed on the temple grounds to steal the sari of the Buddha, Wolsong-daesa, who was the head monk at Tongdosa Temple at that time, safely hid the sari and concealed them from the Japanese. Then, in a second invasion by the Japanese in 1379, Wolsong-daesa took refuge in the capital of Gaegyeong (modern-day Kaeseong, North Korea) with the Buddha’s sari.

During the Imjin War (1592-1598), the sari at Tongdosa Temple were plundered by the Japanese army. However, Grhapati Baegok from Dongnae (in modern-day Busan), who was captured by the Japanese, recovered the sari and escaped to safety with the sari. Afterwards, the famed monk Samyeong-daesa (1544-1610) sent two sari cases to Mt. Geumgangsan (modern-day North Korea). Then, with the Imjin War at an end in 1603, the Geumgang-gyedan (Diamond Altar) was restored after being ruined, and the sari of the Buddha were enshrined, once more, at Tongdosa Temple in their original location at the temple. Ever since the early 17th century, Tongdosa Temple has undergone numerous renovations and rebuilds. In total, the Geumgang-gyedan has been repaired seven times in total including in 1379, 1603, 1652, 1705, 1743, 1823, and 1911 (during Japanese Colonial Rule).

Alongside Haeinsa Temple (The Dharma) in Hapcheon, Gyeongsangnam-do, Songgwangsa Temple (Sangha) in Suncheon, Jeollanam-do, Tongdosa Temple (Buddha) make up the Three Jewel Temples (삼보사찰, or Sambosachal in English) in Korea.

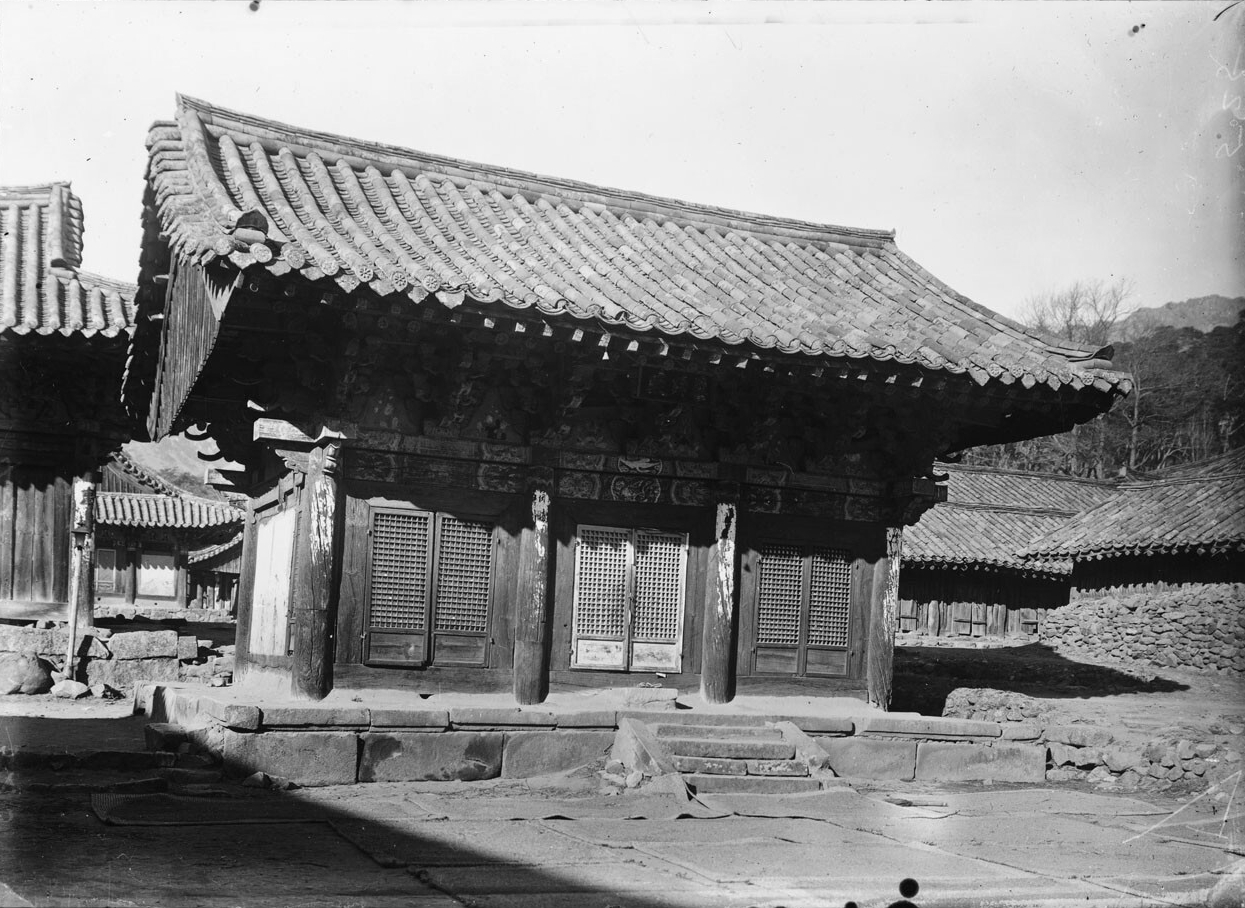

Tongdosa Temple is home to one National Treasure, the Daeung-jeon Hall, and 18 additional Korean Treasures. Of these 18 Korean Treasures, 11 can be found inside the Tongdosa Museum, while the remaining 7 can be found throughout the temple grounds. Tongdosa Temple has one of the largest collections of Korean Treasures at a single temple in Korea.

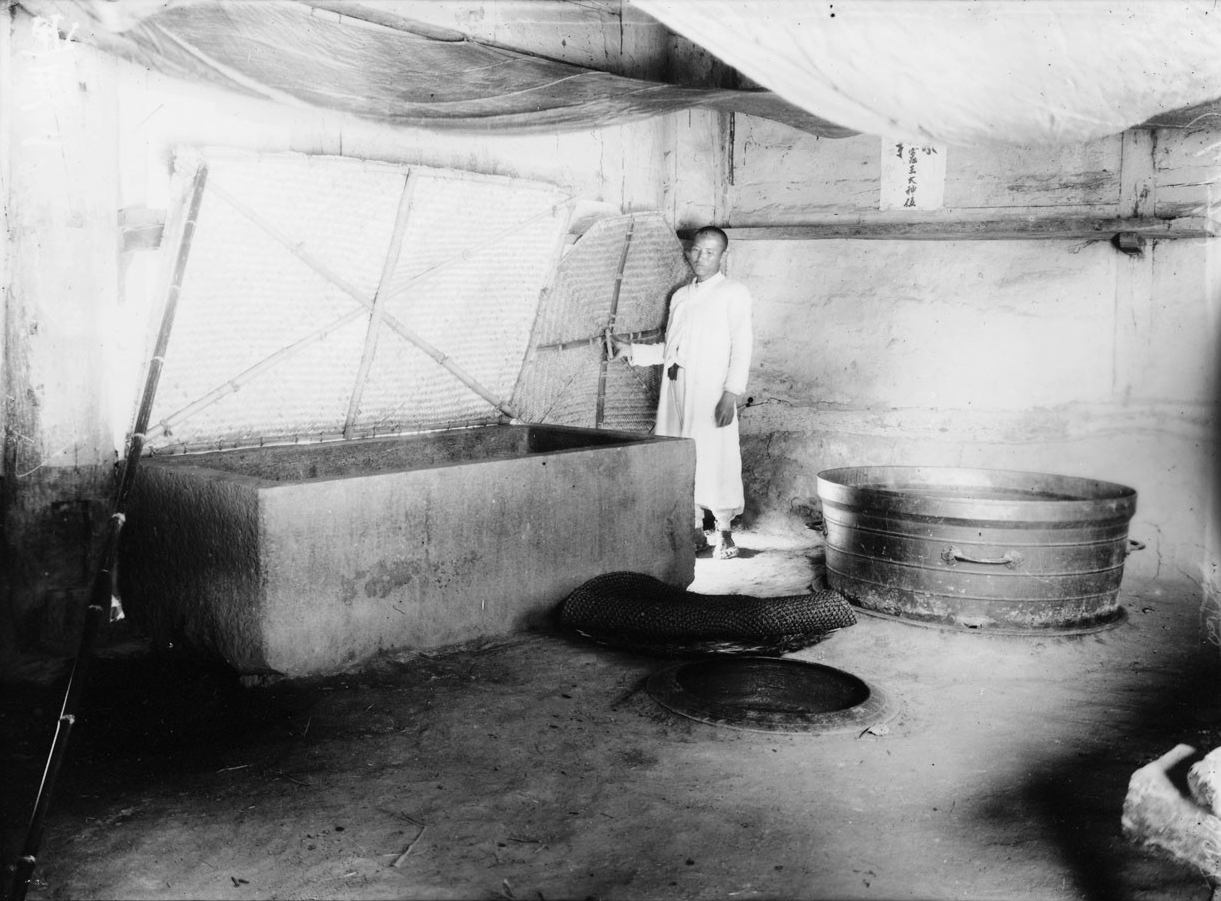

Colonial Era Photography

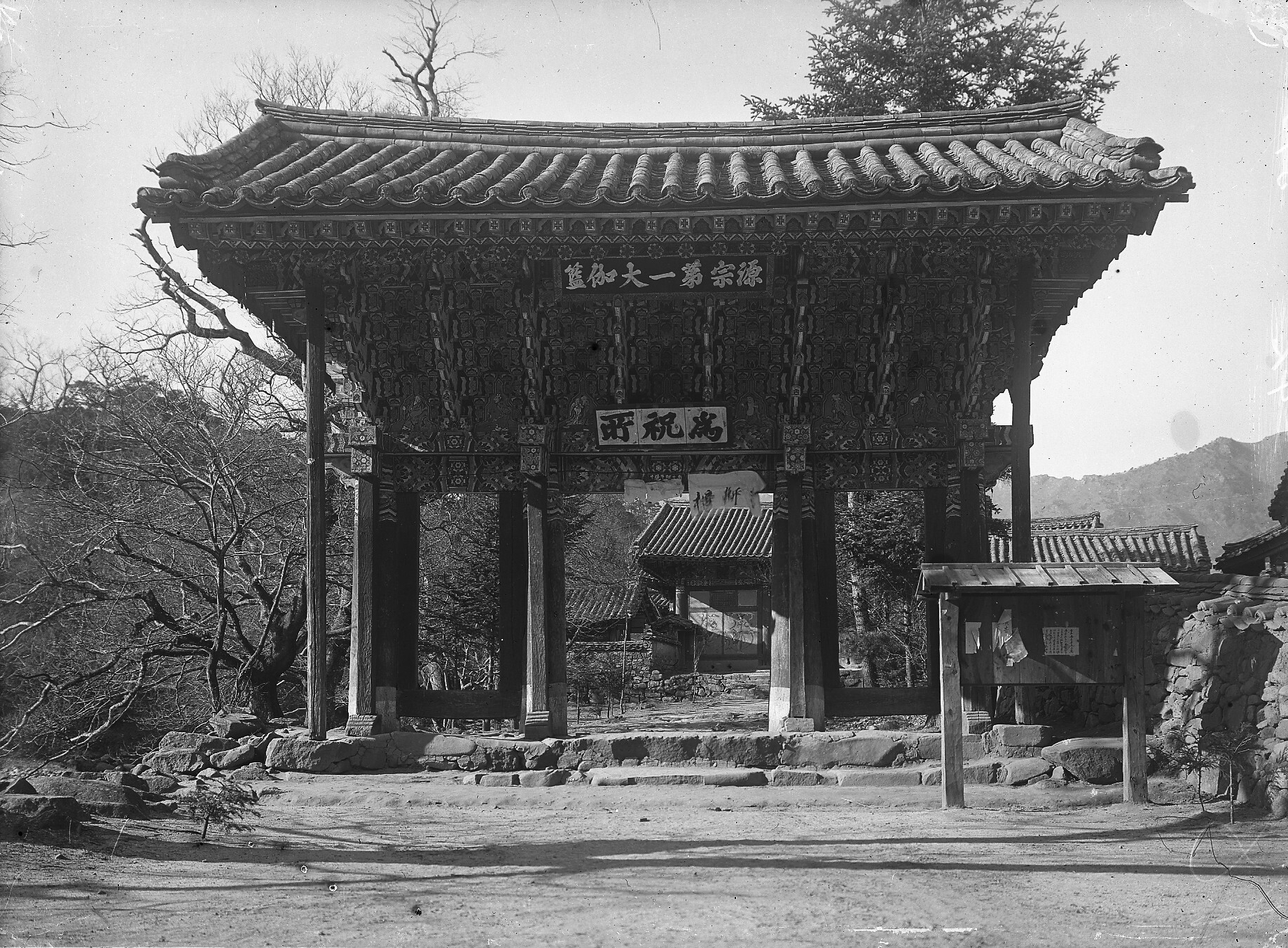

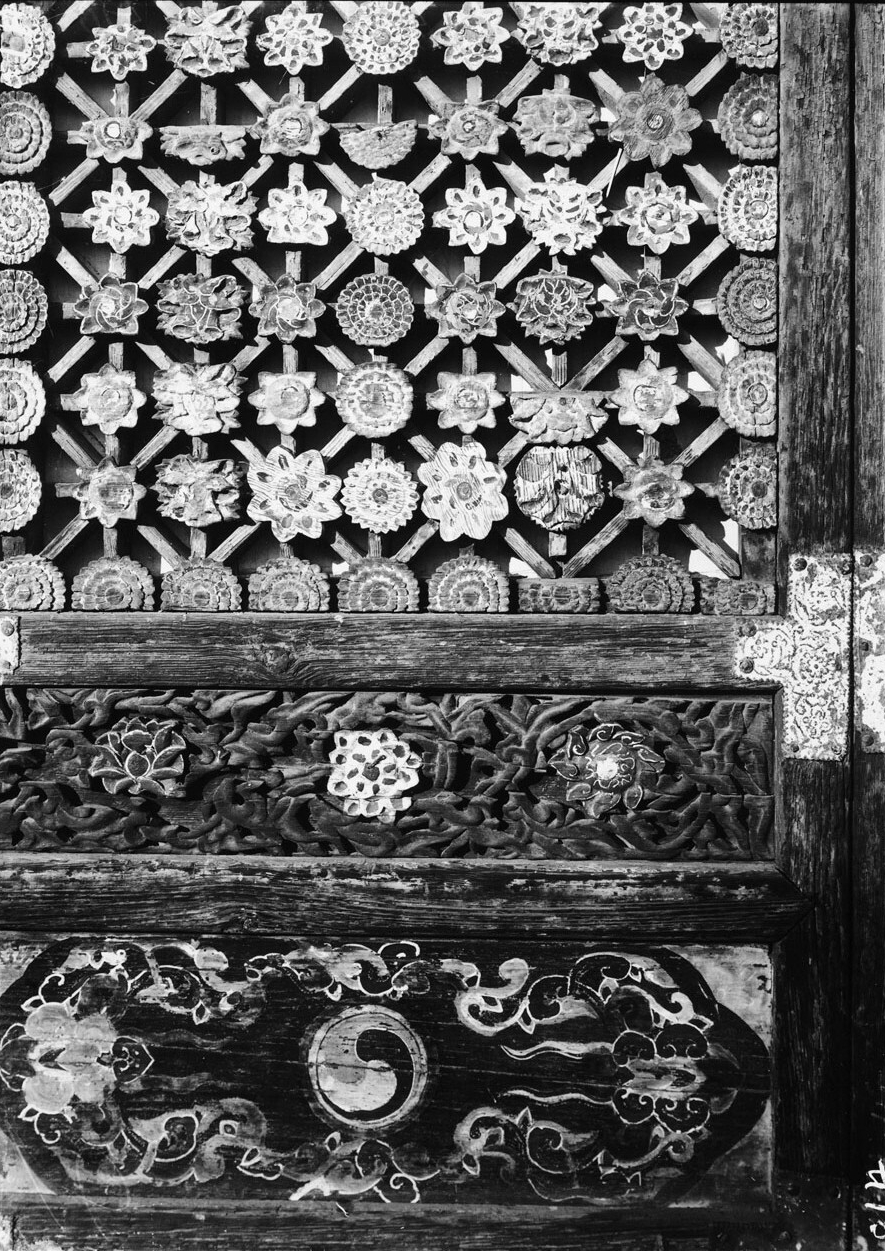

It should be noted that one of the reasons that the Japanese took so many pictures of Korean Buddhist temples during Japanese Colonial Rule (1910-1945) was to provide images for tourist photos and illustrations in guidebooks, postcards, and photo albums for Japanese consumption. They would then juxtapose these images of “old Korea” with “now” images of Korea. The former category identified the old Korea with old customs and traditions through grainy black-and-white photos.

These “old Korea” images were then contrasted with “new” Korea images featuring recently constructed modern colonial structures built by the Japanese. This was especially true for archaeological or temple work that contrasted the dilapidated former structures with the recently renovated or rebuilt Japanese efforts on the old Korean structures contrasting Japan’s efforts with the way that Korea had long neglected their most treasured of structures and/or sites.

This visual methodology was a tried and true method of contrasting the old (bad) with the new (good). All of this was done to show the success of Japan’s “civilizing mission” on the rest of the world and especially on the Korean Peninsula. Furthering this visual propaganda was supplemental material that explained the inseparable nature found between Koreans and the Japanese from the beginning of time.

To further reinforce this point, the archaeological “rediscovery” of Japan’s antiquity in the form of excavated sites of beautifully restored Silla temples and tombs found in Japanese photography was the most tangible evidence for the supposed common ancestry both racially and culturally. As such, the colonial travel industry played a large part in promoting this “nostalgic” image of Korea as a lost and poor country, whose shared cultural and ethnic past was being restored to prominence once more through the superior Japanese and their “enlightened” government. And Tongdosa Temple played a part in the propagation of this propaganda, especially since it played such a prominent role in Korean Buddhist history and culture. Here are a collection of Colonial era pictures of Tongdosa Temple through the years.

Pictures of Colonial Era Tongdosa Temple

1909

Pictures of Colonial Era Tongdosa Temple

1915

Pictures of Colonial Era Tongdosa Temple

1918

Pictures of Colonial Era Tongdosa Temple

1927

Pictures of Colonial Era Tongdosa Temple

Specific Dates Unknown (1909-1945)

Recent comments