You’ll be able to appreciate Korean handwriting more once you get to know each Hangeul letter and have done some exercises. You can truly start having fun with writing in Korean.

Learning more about the different writing techniques is useful, especially when you’ll come across many people’s handwriting. In this article, we will teach you helpful facts to know about handwriting in Hangeul.

Why is learning about Korean writing important?

Nowadays, almost everything is done online, and we often send messages in the form of digital text. However, it is still important to learn about writing traditionally. Here’s why you need to give importance to learning about Korean writing.

Understand different handwriting easily

Being able to utilize handwritten Hangeul fonts and thus also read a local’s handwriting is another handy tool for when you’re in Korea. After all, you could be the master of speaking Korean, and all of that would be useless if you couldn’t read any written word!

Why might handwritten Korean sometimes be difficult to interpret, then? When you write slowly and with focus on each stroke, of course, you’ll come out with handwritten text that could look eerily similar to printed text.

However, most of us try to write as quickly as possible. And often the rush reflects upon our writing, too. And if you’re not at all familiar with what a more rushed handwritten Korean font looks like, you may be in trouble reading some important handwritten texts like doctor’s notes.

Learn different writing styles

Besides being useful to familiarize yourself with handwritten Hangul to interpret the text handwritten by others, it can also be fun to learn different fonts and techniques to write yourself. Once you’re comfortable enough, you’ll have ended up creating a style that expresses your own personality.

Also, handwritten text often looks more aesthetically pleasing than printed text, anyway, so why wouldn’t you want to master it?

How can you better understand handwritten Hangul?

Of course, the main key to understanding handwritten Hangeul is to simply read as many texts that have been handwritten, as well as write as often as possible utilizing different handwriting techniques.

Even if you are primarily practicing by scribbling down your own words, it can provide invaluable experience with learning to understand different handwritten strokes.

In the below section, we’ve introduced you to some techniques with which you can do this practice. Keep them in mind and

How can you make your Hangul handwriting look good?

You might have your own ways of practicing Hangeul in terms of how you write. However, we’ve also listed the two important things that you should consider below.

Practicing with the right materials

The first step to start practicing your handwriting skills for the alphabet – and why not Hangul writing in general – is to get the appropriate paper material for it. Since Hangul is in syllable blocks, you’ll want to utilize squared paper for it, aka 원고지 (wongoji) paper.

There are, of course, certain rules that should be followed when wongoji paper is used, especially if you write official texts such as for exams like TOPIK.

With wongoji paper, you can most of all practice honing your handwriting skills into one that’s clear and correct. However, for personal use, there’s nothing stopping you from using those same pieces of paper to discover your personal handwriting font, too!

Using references for writing styles

Secondly, if you struggle with figuring out how exactly you want your handwriting to look, you can head over online and search for different fonts for handwritten Hangeul. You can then utilize these font examples for your own handwritten texts and see what might feel natural and aesthetically pleasing to you.

And, of course, there’s no need to directly copy any particular font. You can make it yours – and also mash up a few different fonts together to make up your own unique style!

You can either look at your screen and try to match your letters to the characters being shown, or you can create and print word documents similar to when we learned the alphabet as small children and try to recreate the characters like that.

Although you end up not creating a differentiated handwriting font through this, you’ve at least exposed yourself to enough handwritten Hangeul content that you should be able to read a native Korean’s rushed handwriting!

How do handwritten Hangul letters differ from printed ones?

Before you get going and practice on your own, let’s go over which characters, in particular, might look quite different when handwritten. It’s more common for consonants to look different from their printed counterparts than vocals.

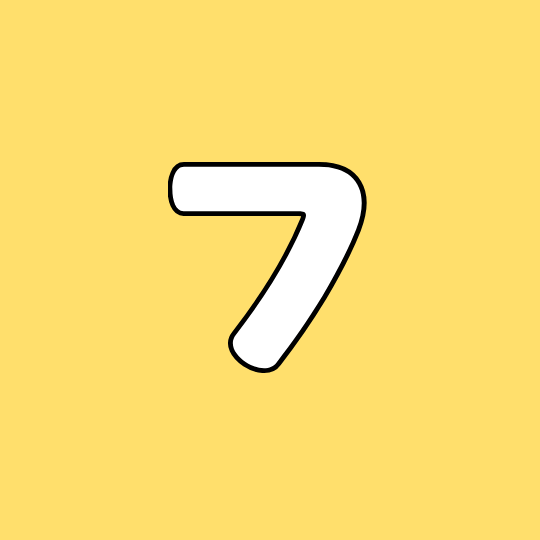

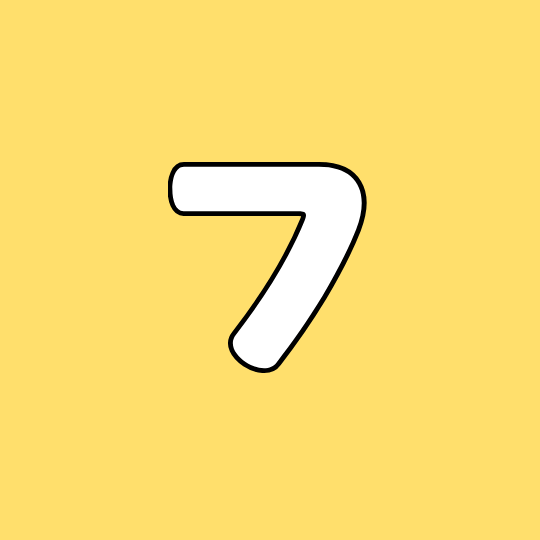

Letter ㄱ

The letter ㄱ is pronounced like “g” or “k,” depending on where in the word it is placed. In the handwritten text, you can sort of illustrate this further by drawing the letter sharper when it’s pronounced as “k” and softer when it’s “g.” For a softer and rounder ㄱ, draw it in one stroke. But for a sharper one, draw the two lines in different strokes.

Letter ㄴ

Although the letter ㄴ never changes in pronunciation, you can apply the same technique here when you want to write it softer or sharper as with ㄱ.

Letter ㄷ

This letter is typically handwritten in two strokes. It is especially with the second stroke, with which you draw the shape ㄴ essentially, that you can influence the shape of the letter ㄴ.

Letter ㄹ

The letter ㄹ is one of the letters changing their shape the most depending on who writes it. Although traditionally written in three strokes, to showcase it similarly to a cursive design, you can only use two strokes. It can look drastically different from the original letter but also really pretty.

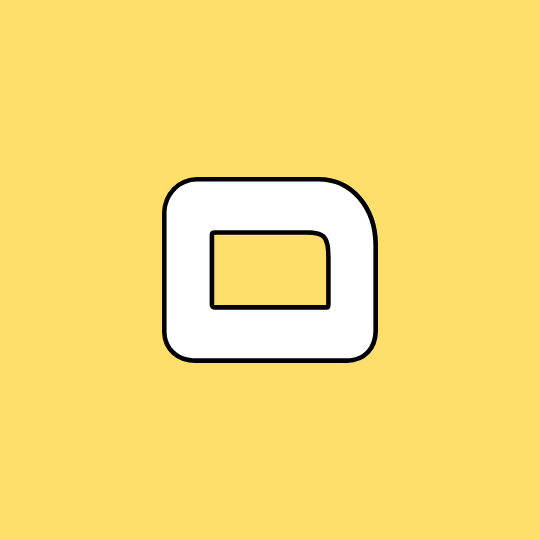

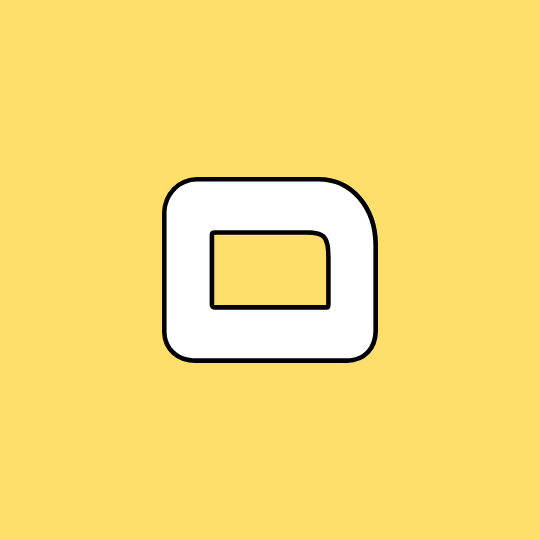

Letter ㅁ

Although ㅁ really doesn’t change shape much and is quite easy to write, you can learn a specific handwritten style, so the ㅁ looks more artistic.

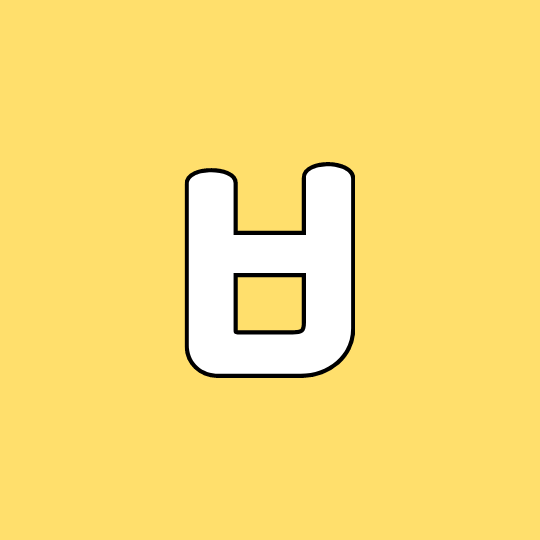

Letter ㅂ

The stroke rules for the letter ㅂ make it quite definite what the letter will look like. However, if you take some artistic liberties, your letter ㅂ might end up looking quite unique. For example, if you try to complete the letter in just two strokes.

Letter ㅅ

Another one that is incredibly simple to write out is the letter ㅅ. You are supposed to draw it in two strokes, but it can easily be written in just one stroke as well. If you want it to look unique, even with two strokes, you can try and leave some space between the two strokes.

Letter ㅍ

Here’s another example of a letter that you can morph into a completely different look with unique handwriting. Specifically, it can look different if it’s written in three strokes instead of the official four.

Letter ㅎ

Finally, ㅎ can also look quite different from what you’re accustomed to when handwritten.

Letter ㅛ

As we mentioned before, vocals tend to vary in handwritten representation slightly less than consonants, but some letters like ㅛ and ㅓ might also look quite different in a handwritten style.

Conclusion

As has been shown above, though the language has quite a specific stroke order and rules, it is possible to morph the characters into a unique look with your handwriting.

Although you might not want to immediately create your own handwriting style and would rather stick to basics, it is important to know what each letter looks like when handwritten so that you can interpret written Korean more.

Based on these examples, do you think it is really difficult or easy to understand Korean handwriting? Let us know in the comments!

The post Korean handwriting – Express your style through written text appeared first on 90 Day Korean®.

Pursuing a restrained US foreign policy is compatible with helping Ukraine, because restraint still takes threats seriously and Putin is pretty obviously one.

Pursuing a restrained US foreign policy is compatible with helping Ukraine, because restraint still takes threats seriously and Putin is pretty obviously one.

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

There has a been a pretty vibrant debate in South Korea over building an indigenous aircraft carrier. That debate has been especially resonant where I live – Busan – because it would probably be built here.

There has a been a pretty vibrant debate in South Korea over building an indigenous aircraft carrier. That debate has been especially resonant where I live – Busan – because it would probably be built here.

Recent comments