Daewonsa Temple – 대원사 (Boseong, Jeollanam-do)

Temple History

Daewonsa Temple is located in Boseong, Jeollanam-do to the north of Mt. Cheonbongsan (611.7 m), which means “Phoenix Mountain” in English. Purportedly, the temple was built by the monk Ado in 503 A.D. in the Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C. – 660 A.D.). During Later Silla (668-935 A.D.), Daewonsa Temple was one of eight major temples in the Nirvana Order. Also, it makes the claim that it was one of the Five Gyo (doctrinal) and Nine Seon (meditative) temples.

During the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), Jajin Wono-guksa, who helped finish the Koreana Tripitaka engravings at Seonwonsa Temple on Ganghwa-do Island, then traveled down to Daewonsa Tepmle to help re-build shrine halls and monks’ living quarters at the temple in Boseong in 1250.

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), in 1759, Hyeon Jeong-seonsa rebuilt twelve of the buildings and shrine halls at Daewonsa Temple. Later, between October and November of 1948, and during the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion, the entire temple complex, and all twenty of its buildings, were completely destroyed at Daewonsa Temple except for the Geukrak-jeon Hall.

In 1990, the Daewonsa Restoration Committee was formed and the temple grounds were rebuilt once more. In total, Daewonsa Temple is home to two Korean Treasures. They are the Mural Paintings in Geungnakjeon Hall of Daewonsa Temple, Boseong (Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva and Buddhist Monk Bodhidharma), which is Korean Treasure #1861 and the Buddhist Paintings of Daewonsa Temple, Boseong (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and Ten Underworld Kings). In addition to these Korean Treasures, Daewonsa Temple is home to a pair of Jeollanam-do Tangible Assets.

Also of interest is the six kilometre long road leading up to Daewonsa Temple, which is called The Cherry Road to Daewonsa Temple. It was selected as one of the one hundred most scenic roads in Korea. And according to Pungsu-jiri, the road is considered like an umbilical cord, the temple is considered to be within the uterus, while the peak of the mountain is meant to be a phoenix sitting upon its nest.

Temple Legend

According to a temple sign at Daewonsa Temple, there was a monk named Kim Jijang. Kim Jijang, whose birth name was Kim Gyogak (696-794 A.D.), was the son of King Seongdeok of Silla (r. 702 – 737 A.D.), so Kim Jijang was born a prince in 696 A.D. Kim Jijang became a monk when he was twenty-four years old, and he received the Buddhist name of “Jijang.” At the time of taking his precepts, Jijang received a white Sapsali, which is a Korean indigenous dog. He also received Korean pine tree seeds, rice seeds, millet, and tea. He then moved to China. While in China, he stayed near Mt. Guhwa, which is known as Mt. Jiuhua in China. There, he practiced the life of a monk, and he taught people Buddhist teachings.

At the age of ninety-nine, and after living for seventy-five years in this remote part of China, on July 30th, 794 A.D., Kim Jijang entered Nirvana. Upon his departure, he left a message that said, “Please don’t cremate my body. Just put my body into a stone box. And please open the box after the new year. If the body has not decayed, then paint my body gold.”

After three years, people saw Jijang’s body, and they saw that his face still looked alive and his skin looked soft. In fact, his body emitted the smell of incense from it. So in 797 A.D., people put his body into a shrine at Mt. Guhwa. This shrine is now called “Yukshinbo-jeon – 육신보전,” and it means “Preserving the Body Hall” in English. It’s believed that Kim Jijang was a reincarnation of Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife).

In 2001, Daewonsa Temple built a shrine hall called the Kim Jijang-jeon Hall to honour this Silla monk. They also enshrined three images of Kim Jijang inside this shrine hall on the main altar. In addition, they painted fourteen murals depicting the life of Kim Jijang around the exterior walls to this temple shrine hall.

Temple Layout

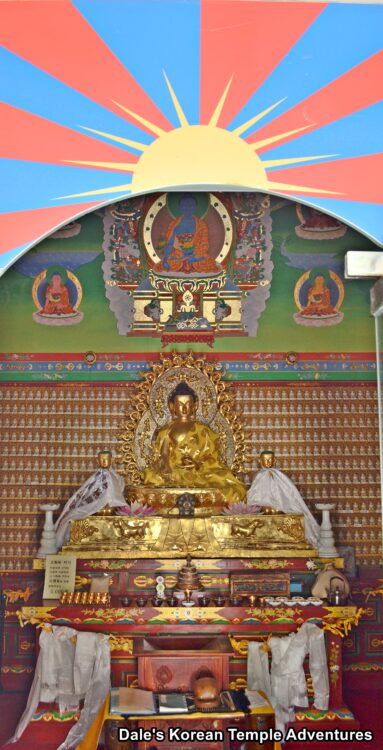

You’ll first make your way up the beautiful and scenic six kilometre long stretch of road that leads up towards Daewonsa Temple. When you do finally arrive at the temple parking lot, you’ll notice the Daewonsa Tibetan Museum. This museum, which seems a bit out of place, opened in 1987. Admission to the museum is 3,000 won for adults and 2,000 won for children. The two-story museum is filled with beautiful Tibetan statues and paintings. And out in front of the Tibetan Museum is a fifteen metre tall white pagoda that was first constructed in March, 2002. Housed inside this pagoda, inside the base, is a triad of Tibetan statues centred by Yaksayeorae-bul (The Medicine Buddha, and the Buddha of the Eastern Paradise). This statue is backed by a blue central image of Yaksayeorae-bul and surrounded by seven additional images of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. And painted on the top of the ceiling of this chamber is a Tibetan mandala.

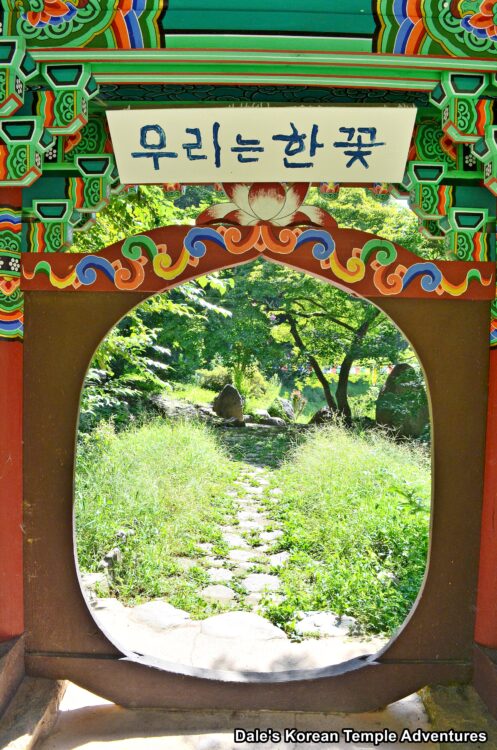

To the right of the Tibetan Museum and pagoda, and across the temple parking lot, you’ll find Daewonsa Temple’s colourful Iljumun Gate. After passing through the Iljumun Gate, and to your right, you’ll find a circular gate that reads “우리는 한꽃” on it. In English, this means “We Are All Flowers” in English. Through this gate, you’ll find a mountain stream and a clearing with beautiful, mature trees.

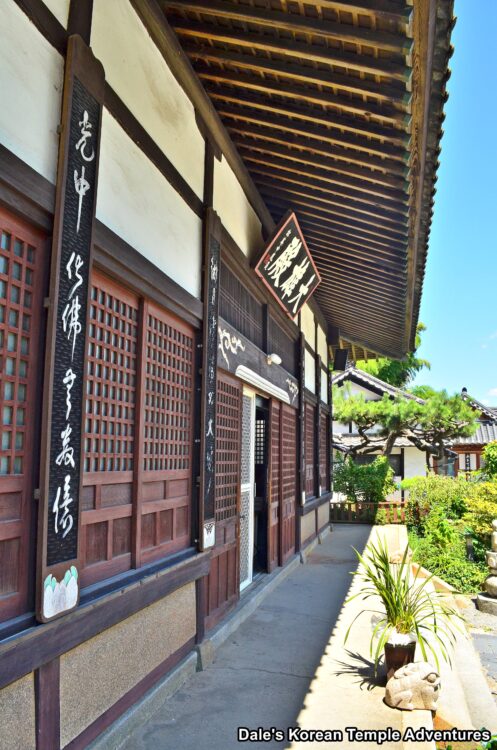

Passing back through this circular gate, and now standing next to the Iljumun Gate, you’ll make your way up towards a three-in-one entry gate. On the first floor of the two-story structure, you’ll find wooden reliefs dedicated to the Four Heavenly Kings. And joining these reliefs is the temple’s administration office. The second story of the structure acts as the Boje-ru Pavilion. Rather interestingly, and adding to the overall peculiar feel of the temple, is the temple’s Mokeo, or “Wooden Fish Drum” in English, hanging from the ceiling of the structure, as well as a pair of monk’s shoes.

Beyond this three-in-one entry gate is a statue dedicated to Podae-hwasang (The Hempen Bag) to your right, as well as a historic stone Buddha shrine reminiscent of the one found at the neighbouring Unjusa Temple. These hard to find historic shrines have a rectangular shape. And inside the shrine, inside the adjoining chambers, you’ll find a pair of stone Buddha statues seated back to back.

To the left of this outdoor stone Buddha shrine, and before walking over the diminutive stone bridge to gain entry to the main temple courtyard at Daewonsa Temple, are two rows of stone monk statues with red knitted caps on their heads. These are meant to be a sign for prayers for children that have died.

Across the small stone bridge and through another circular entry gate, you’ll now enter the main temple courtyard. To your immediate right, you’ll find the temple’s Jong-ru (Bell Pavilion) with a large golden bell inside it.

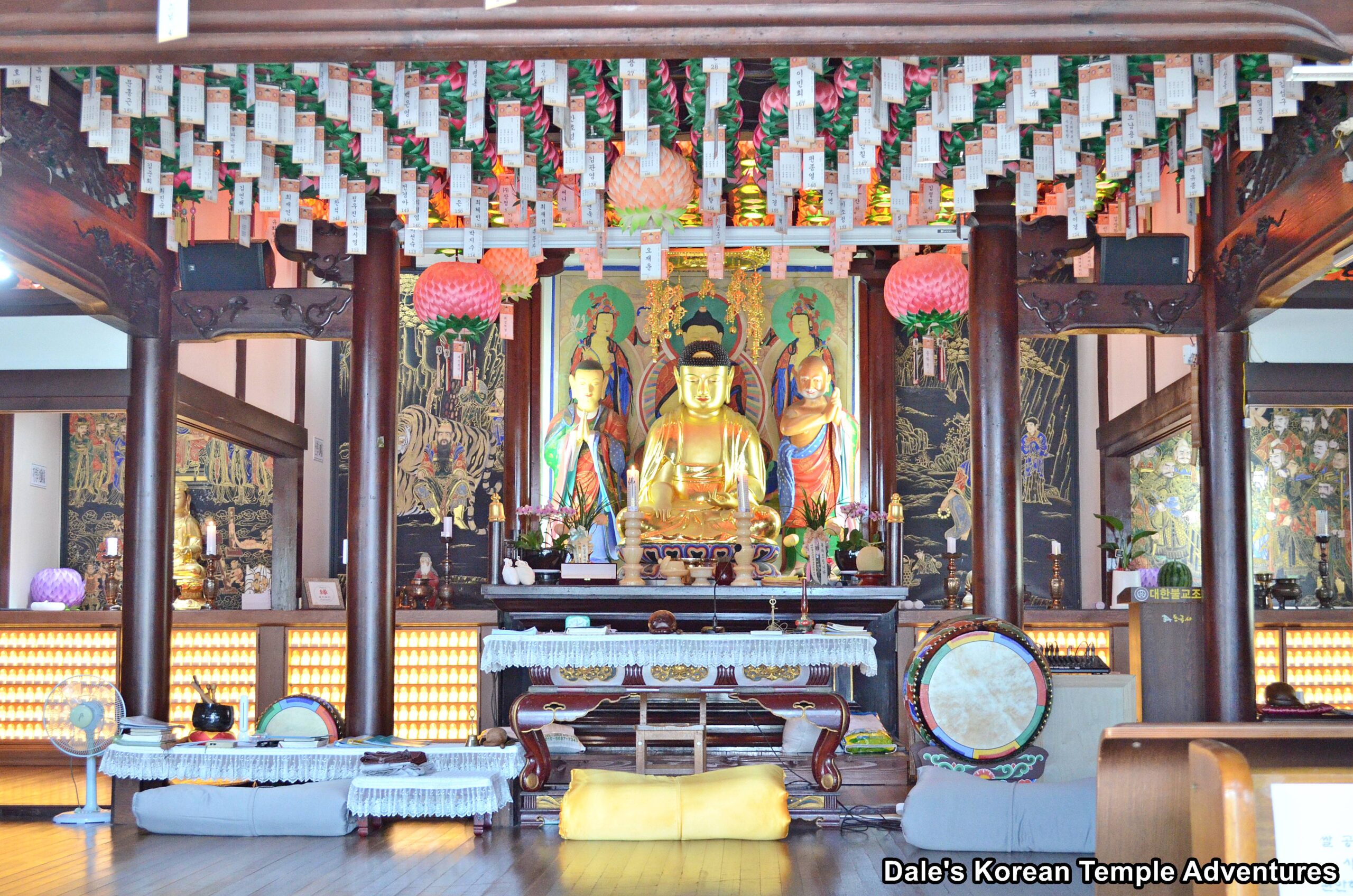

Straight ahead of you is the temple’s main hall, which is the Geukrak-jeon Hall at Daewonsa Temple. It’s unclear when the Geukrak-jeon Hall was first built, but it dates back to at least the reign of King Sukjong of Joseon (r. 1674-1720), when the famed murals painted inside the Geukrak-jeon Hall were painted. These murals, which are officially known as Mural Paintings in Geungnakjeon Hall of Daewonsa Temple, Boseong (Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva and Buddhist Monk Bodhidharma), and are Korean Treasure #1861. These murals are placed high on either side of the east and west walls of the Geukrak-jeon Hall. The western wall has the image of Gwanseeum-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Compassion), or Avalokitesvara in Sanskrit. This image of Gwanseeum-bosal is dressed in a white robe and seated on a lotus flower floating on the waves. In the background of this mural, you’ll find rocks and bamboo with a dongja (attendant) behind Gwanseeum-bosal with a blue bird in his arms. And on the eastern wall, you’ll find the mural dedicated to the Bodhidharma. In this mural, the Bodhidharma is joined by the armless Huike (487-593 A.D.). Both of these murals are wonderful examples of Buddhist artistry in the late Joseon Dynasty. And the painting style is that of Uigyeom, who was an active painter in the region in the mid to late 18th century.

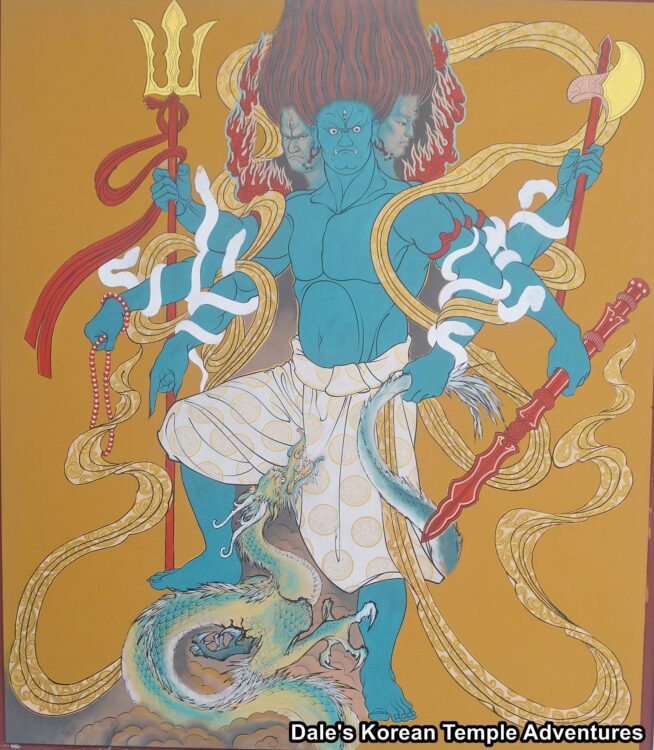

There are other various murals that adorn the interior of the Geukrak-jeon Hall that are similar in age to the two aforementioned murals. Resting on the main altar is a triad centred by Amita-bul (The Buddha of the Western Paradise). This central image is joined on either side by Gwanseeum-bosal and Daesaeji-bosal (The Bodhisattva of Wisdom and Power for Amita-bul). And just below the historic mural dedicated to Gwanseeum-bosal, you’ll find a rather long, red Shinjung Taenghwa (Guardian Mural). And to the right of the main altar, and below the large, historic mural dedicated to the Bodhidharma, you’ll find a mural dedicated to Chilseong (The Seven Stars).

To the right of the Geukrak-jeon Hall, you’ll find the temple’s Myeongbu-jeon Hall, which usually houses the Korean Treasure Buddhist Paintings of Daewonsa Temple, Boseong (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and Ten Underworld Kings). However, since the Myeongbu-jeon Hall is currently under renovation, I’m not sure where this painting is currently. And out in front of the Myeongbu-jeon Hall is a large shrine dedicated to Jijang-bosal (The Bodhisattva of the Afterlife). In one hand, the large, central image of Jijang-bosal holds a golden staff in his right hand and a baby in his left. All of the other surrounding stone statues wear red caps on their heads much like at the entry of the temple grounds.

To the left of the Geukrak-jeon Hall, you’ll find a shrine hall and stupa dedicated to Jajin Wono-guksa. This stupa is Jeollanam-do District Tangible Asset #35. The foundation of the stupa has a lotus design on it, and the body of the stupa has Bodhisattvas and the Four Heavenly Kings adorning it, as well as hanja characters that say “The stupa in memory of the purity of Jajin Wono-guksa” written on the front side. And on the back side of the stupa, you’ll find the hanja characters for “Om, Ah, Hum,” which is from the Mahavairocana Tantra written on it. This stupa is the oldest artifact at Daewonsa Temple. And inside the adjoining hall is a memorial shrine hall dedicated to Ado, who was the founder of the temple. And housed inside the Ado-yeong-gak Hall is a painting of the historic monk.

Up the mountainside, and a bit hidden to the right at the lantern, you’ll find the temple’s Sanshin-gak Hall. Housed inside this secluded shaman shrine hall is the rather distinctive image of a female Sanshin (The Mountain Spirit). There are both a statue and wooden relief dedicated to this shaman deity housed inside the Sanshin-gak Hall.

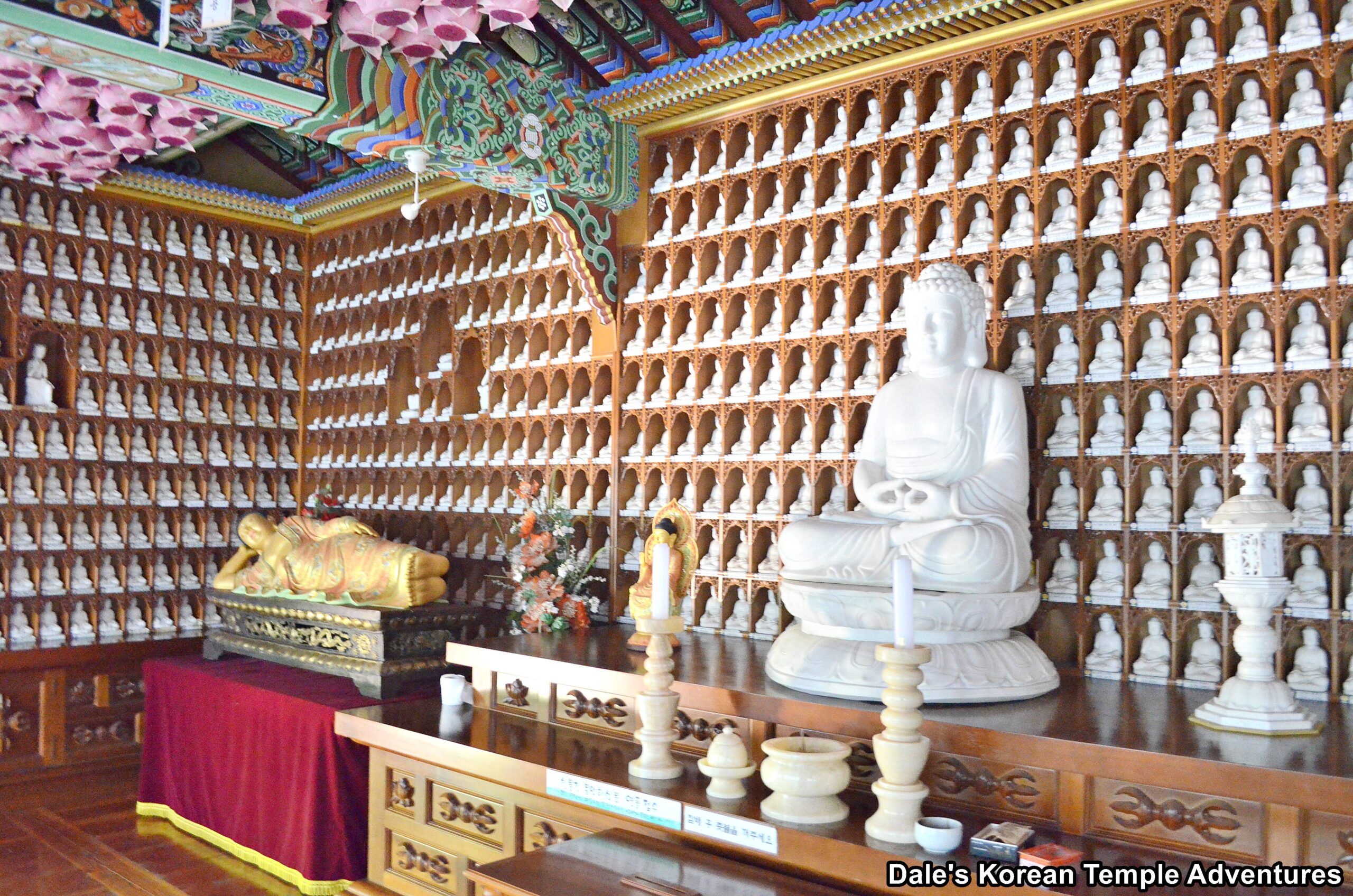

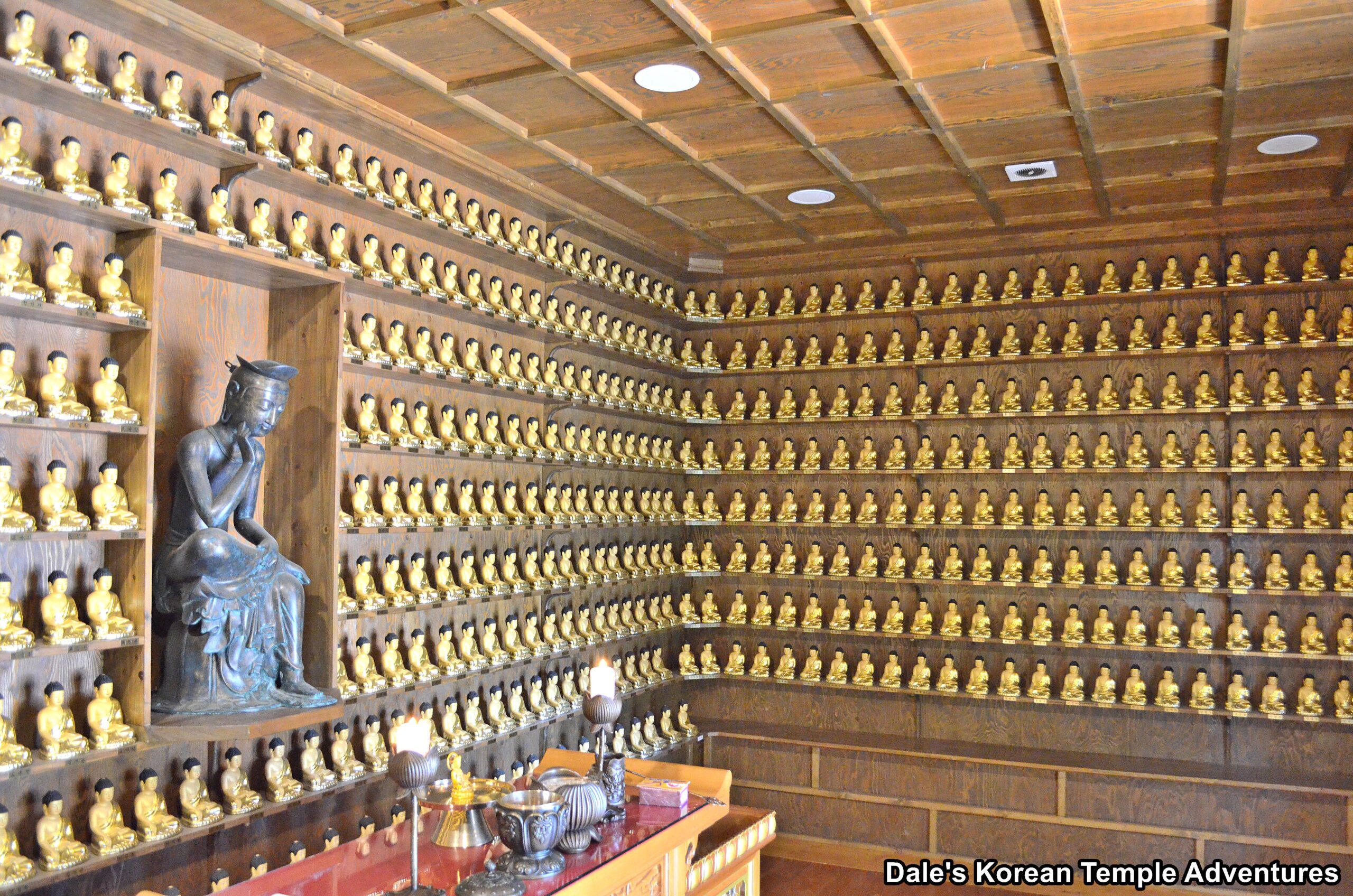

Back at the main temple courtyard, and to the right of the outdoor shrine dedicated to Jijang-bosal, you’ll find a pair of shrine halls. The first to the right is the Cheonbul-jeon Hall. You’ll have to duck down when entering the Cheonbul-jeon Hall because the entry door is purposely low so you have to bow down when entering this temple shrine hall. Housed inside the Cheonbul-jeon Hall, other than the one thousand white statues of the Buddha that gives the shrine hall its name, is a larger white statue of Seokgamoni-bul (The Historical Buddha) on the main altar. To the left lays the statue of a Reclining Buddha.

And to the left of the Cheonbul-jeon Hall is the Kim Jijang-jeon Hall, which is directly related to the legend associated with Daewonsa Temple. Surrounding the exterior walls to the Kim Jijang-jeon Hall are fourteen images reenacting the adventures of Kim Jijang. Stepping inside this temple shrine hall, you’ll find a triad of crowned Jijang-bosal images on the main altar. And to the left of this main altar, you’ll find another golden image of Jijang-bosal; but this time, Jijang-bosal is atop a golden haetae. And on the far right wall is a large mural dedicated to Jijang-bosal.

How To Get There

From the Boseong Bus Terminal, you’ll need to board one of three buses to get to Daewonsa Temple. Your choices are Mundeok – 문덕 #80-1, Mundeok – 문덕 #80-3, or Mundeok – 문덕 #80-6. Now this is the rub, you’ll need to take any of these buses for an hour and a half from the Boseong Bus Terminal, which is fifty-one stops. After fifty-one stops, or an hour and a half, you’ll need to get off at the “Juksan – 죽산” bus stop, which is also called “Daewonsa Sumi Gwangmyeong-tap – 대원사 수미 광명탑.” From this stop, you’ll need to walk about ten minutes, or 700 metres, to get to Daewonsa Temple.

Overall Rating: 7.5/10

Daewonsa Temple in Boseong, Jeollanam-do is a rather peculiar temple with a peculiar feel to it. Starting with the temple’s legend, continuing onto the monk shoes at the Cheonwangmun/Boje-ru, and on towards the Kim Jijang-jeon Hall and the rows of red capped statues, Daewonsa Temple definitely is original. There are other unique features like the Tibetan Museum at the entry and the “우리는 한꽃” near the Iljumun Gate, as well. But it also has some startlingly original features like the historic, large murals housed inside the Geukrak-jeon Hall, the stupa dedicated to Jajin Wono-guksa, and the outdoor stone shrine with the twin Buddhas inside it. There’s definitely a lot of things to see and explore at the out of the way Daewonsa Temple in Boseong, that’s for sure!

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Learn to read Korean and be having simple conversations, taking taxis and ordering in Korean within a week with our FREE Hangeul Hacks series:

Recent comments