Taking some time before my next adventure undoubtedly gave me the space to process my year in China, and to work through the pile of battered notebooks that make up my travel journals. I’m writing this from Seoul, South Korea, about to take up a new contract teaching in the wilds of Gangwon province, but before I dive into the next chapter I wanted to write something about my trip to Xinjiang, which was probably the most important turning point of my time in China.

I left a piece of my heart in this vast province, encompassing scorching desert, lush grasslands and the towering mountains of the Kharkoram Pass. I took the trip around 6 months into my time in China, when I was really struggling: I felt I was bashing my head against a brick wall with the language and culture; everything I did seemed to be a mistake and I was offending or offended in every interaction. This combined with a bike accident, a burglary and the general daily grind of culture shock had left me feeling tense, irritated and mistrustful, a state I was unused to and disliked. For the first time in my life, I realised, I was homesick. Painfully, desperately homesick for silence, anonymity and understanding; for green space, clean air and a sky that I could see.

It was in this state that I landed in Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi, and immediately felt I was in a completely different country: the indiginous Uighur people are recognisably central Asian in appearance, largely Muslim, and speak a Turkic language written in Arabic script. I took trips to the sweeping grasslands north of the city and to the endless dunes and ancient ruins of the Taklamakan desert to the south. A 24-hour train journey took me to Kashgar, the oasis city and Uighur heartland which was also the last stop in China on the Silk Road. Here I was woken every morning by the prayer call. The winding backstreets and bazaars boasted stalls laden with carpets, headscarves and spices; gone were the teahouses, replaced by sherbet stands where locals gathered to ward off the searing desert heat. The air of the night market was alive with music, chatter and the scent of cumin, cinnamon and roasting lamb.

From Kashgar, I took a minibus high into the Karkoram pass on the border with Pakistan. A central Asian X-Factor- type show was playing on the bus’ television, and as we wound our way up the treacherous terrain, the slopes of K2 rising in the distance, the locals joined in a rendition of ‘My Heart Will Go On.’

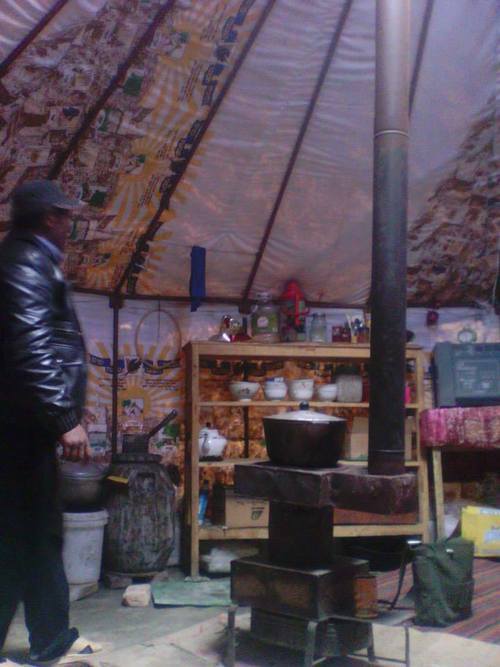

The bus dropped me off on the deserted shores of mountain lake Lake Karakul, where I stayed for the night in a yurt with only the wild camels for company. The next day, I learned to ride Kyrgyz-style (one-handed, no protection, no surrender), from a local herdsman whose mother fed me a meal of yogurt and bread when the lesson ended back at his home village. Before heading back to Kashgar and ultimately Sichuan, I hitched a lift through the peaks to the last town before the Pakistani border, gazing at the stark, beautiful landscape and shivering in the chill of the mountain air.

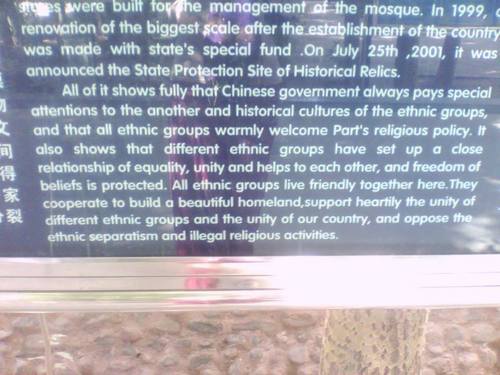

The reason for the huge cultural differences between Xinjiang and most of the rest of China is a sad and predictable one: Xinjiang pretty much is its own country, but the fly in the massive oil field is that it is home to huge reserves of the black stuff, producing vast amounts of gas and petrochemicals in addition, so China is hanging onto it as tightly as possible. Unsurprisingly, tensions run high. The largest province in China (over seven times the size of the UK), Xinjiang has long struggled for independence with supporters of an independent state East Turkestan being ruthlessly suppressed by Chinese authorities. One strategy of Beijing’s has been to encourage and incentivise Han migration to the region, meaning that the population is now close to even Han and Uighur, with the Han noticeably in almost all positions of power. The tension is palpable: my Han Chinese colleagues thought I was insane to even think of visiting, telling me Xinjiang was dangerous and full of terrorists (it probably didn’t help that Beijing had in fact recently published reports of 'terrorist attacks’ on police in Kashgar, which many outsiders read as a convenient justification for the capital’s repressive tactics).

In truth, Xinjiang is probably not a pleasant place to travel if you are Han Chinese: the them and us mentality runs strong, down to locals refusing to keep Beijing Time (travellers are often caught out by by shops opening and long distance buses departing 2 hours later than expected). Mandarin is referred to as Han hua (Han language) and the Uighur population, who saw themselves as foreign to the Han as I was, openly criticised the Chinese people, culture and government to me in English and Mandarin, whilst pretending not to understand the questions or comments of Han travellers. The unexpected side effect of this tension was that, as a white European, I attracted nothing like the scrutiny and negative attention that had been weighing me down in Sichuan. Between the ever-present hostility of the two sides, I could slip relatively unseen and without comment for the first time in six months. When I spoke Mandarin, I found it had become a lingua franca, a tool for communication I could enjoy learning, rather than a cause of anxiety: Uighur locals seemed to take the attitude that we were both speaking a foreign language and there was a goal to the conversation that it was important to reach, rather than that I was bastardising their native tongue and therefore a cause for ridicule or frustration.

I returned to Sichuan renewed, rejuvenated by silence, nature, blue sky, and having fallen head over heels for a place again. Before I’d left, I’d begun to think that I had failed, really: that my oft-stated love of exploring new places and cultures had been naive - if it were true, why was I struggling so much with China? Xinjiang did not just give me time and physical space to appreciate the enormity of the move I’d made, to a culture with no shared roots with mine which placed little to no value on many of the things I held to be important, and which for reasons beyond my control was pretty damn cagey about opening itself to me. My love affair with the region also reminded me how much I did live for travel and adventure - it was just that Sichuan was the most challenging version of this I’d yet come up against. These factors saw me through the second half of my stay. I resolved to set myself a couple of travel-related goals (the sponsored bike ride to Songpan and another extended trip, overground through Yunnan to Hong Kong) and a couple of social ones (invest in language learning and Chinese friendships). Both bore fruit, and though my time in Sichuan was definitely the steepest learning curve of my life so far, it ultimately opened more doors to me than I could have imagined. As I prepare to immerse myself in another new culture, I feel that wherever I go the 'Xinjiang Effect’ will stay with me, spurring me on when the going gets rough.

GoEastMyChild.Tumblr.com

Wanderings and Ramblings of an ESL teacher currently based in a tiny mountain town near the North Korean border.

Recent comments