This is a re-post of an essay I wrote for The National Interest a week ago.

Basically my argument is that even if you are a hawk on China and see it as an emerging competitor or even threat to the US, the clash of civilizations framework is a weak analytical model by which to understand Sino-US tension.

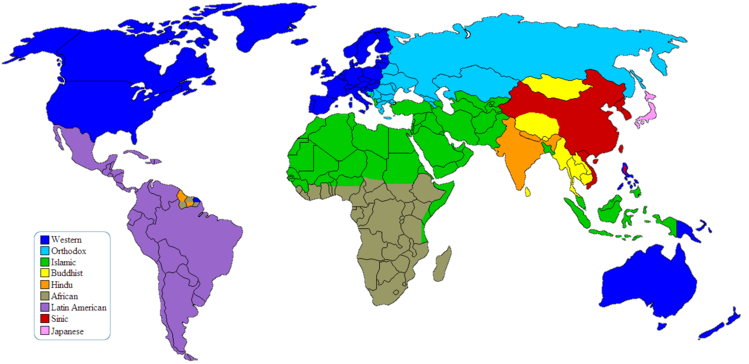

The big problem is that Huntington builds his civilizations everywhere else in the world around religion, but in East Asia he can’t, because that would make China and Japan – who are intense competitors – allies in a Confucian civilization. Making Japan and China allies would be ridiculous, so Huntington can’t use Confucianism as a civilization, even thought that so obviously fits his model for East Asia. Hence, Huntington falls back on national labels, identifying separate ‘Sinic’ and ‘Nipponic’ civilizations. This ad hoc prop-up of the theory undercuts Huntington’s whole point of arguing that national distinctions are giving way to civilizational ones and that therefore we should think of future conflicts as between civilizations, not nation-states. Well, apparently East Asia didn’t make that shift; conflict here is still nationalized. So

There are other issues I bring up as well, but that’s the main problem. Please read the essay after the jump…

Kiron Skinner, the Director of Policy Planning for the US State Department, ignited a controversy last week when she analogized Sino-US competition to a clash of civilizations. There has been a good deal of pushback from international relations academics (here, here). Many noted that Samuel Huntington’s famous thesis (article, book) has not actually been born out much. There have not in fact been wars since his writing that have been as epochal as the ‘civilizational’ label would suggest. And Skinner’s particular comment that China will be America’s first “great power competitor that is not Caucasian” sparked a lot of extra controversy that ‘civilization’ was being use as rhetorical cover for the Trump administration’s persistent flirtation with white nationalism.

But one problem in all this not yet pointed out is how poorly Huntington’s model actually fits the dynamics of conflict in East Asia. The argument got its greatest boost from the post-9/11 war on terrorism. There, religious conservatives – on both sides ironically – saw the conflict as much as a millennial clash between Islam and Christianity, as between the US and rather small, if radical, terrorist networks. Huntington’s book was even re-issued with a cover depicting a collision between Islam and the US. But in East Asia, the thesis really struggles.

The central variable defining Huntington’s civilizations is religion. This is why the argument feels so intuitive for the war on terror, where religion is a powerful, obvious undercurrent. But in East Asia, religious conflict was never as sharp as in the West, Middle East, and South Asia. Nor did religion define polities in East Asia as sharply. Confucianism and Buddhism were obviously socially influential, but they generated nothing like the wars of the Reformation or the jihads of early Islam.

So while much of the world is coded by Huntington via religion, he struggles to use that in East Asia. Instead, he falls back on nationality mostly – coding China, the Koreas, and Vietnam as ‘Sinic’ and Japan as ‘Nipponic.’ He also suggested a Buddhist civilization in southeast Asia, as well as Mongolia and Sri Lanka.

All this is analytically pretty messy, however interesting. First, the most obvious benchmark for Huntington to use in East Asia, since he focuses on the world’s major religions elsewhere, is Confucianism. Whether coded as a social philosophy or religion, there is little doubt that Confucius’ writings had a huge impact on China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. But if Huntington had done the obvious and tagged a Confucian civilization including these four players, he would have made the laughably inaccurate argument that those states are natural, i.e., cultural/religious/civilizational, allies.

In reality of course, there is a lot of traditional national interest-style conflict – the kind Huntington says has been replaced by civilizational bloc-building – in the Confucian space. China and Japan are obvious competitors, and the East China Sea is a serious potential hot-spot now. The Koreas are still very far apart ideologically, and neither feels much affective affinity for China or Japan. And China and Vietnam also sliding toward competition in the South China Sea.

So Huntington is stuck; his model does not work in northeast Asia. So to save it, he carves out Japan as a separate civilization defined by nationality, not religion, with little explanation. He then lumps the Koreas and Vietnam under a Chinese-nationality defined ‘Sinic’ civilization, which, in my teaching experience, Korean and Vietnamese readers find either typical American ignorance or vaguely offensive.

The Buddhist civilization of southeast Asia struggles analytically too. Do Mongolia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka have enough in common to bin together? Why isn’t South Korea, where Buddhism was long influential and still very much alive, put into this civilization? Do these states communicate or cooperate with each other in any way that much reasonably defined as ‘buddhistic’? The answer is almost certainly that Huntington did not know or really care that much – likely as he did not know what to do with non-Arab Africa, so he just labels it all one ‘African’ civilization and moves on.

The thesis was really designed to explain the collisions in southeastern Europe (the Balkan wars of the 1990s) and the Middle East between Muslim-majority states and their neighbors, and this is where it continues to be most persuasive when taught. In east Asia though, it falls down pretty quickly. The units of analysis (civilizations) are not constructed in that region around the variable (religion) which Huntington uses elsewhere, and the conflicts of the region have little to do with religion, because organized religion was not as influential in East Asia’s political past as it was elsewhere.

So if this is to be the Trump model for US foreign policy – and it certainly seems to be the administration’s preferred mode to address Islam – it will lead to bizarre predictions and behaviors. The ‘Confucians,’ Buddhists, and East Asian ‘non-Caucasians’ are not going to ally against the United States. China, for all its ‘Sinic’ cultural difference from the West is also, obviously, deeply influenced by Western political thought – most obviously Marxism-Leninism, and, today, capitalism.

We may well fall into a cold war with China; prospects for a benign, or at least transactional, Sino-US relationship are narrowing. But there is no need to over-read that competition as an epochal civilizational clash and thereby make it worse and more intractable. That kind of thinking applied to 9/11 lead to wild overreaction, as we read salafist-jihadist networks as a far greater threat than they were. If we do that with China, which really is very powerful, our competition with it will be that much sharper and irresolvable.

Assistant Professor Department of Political Science & Diplomacy Pusan National University @Robert_E_Kelly |

|

Recent comments