Why Gangnam is bad and why Psy’s ‘Gangnam Style’ might not be so bad

By R.M. Adamson

“Gangnam Style”

I’m a guy

A guy who is as warm as you during the day

A guy who one-shots his coffee before it even cools down

A guy whose heart bursts when night comes

That kind of guy

Coffee shops serve as backdrop for romantic and emotional scenes in a lot of hallyu (“Korean Wave”) television series, those melodramas that have earned popularity in neighboring countries such as China and Japan, and so it might be only small surprise that the beverage plays a role in the recent K-pop hit song and video, “Gangnam Syle,” by the performing artist who goes the handle, Psy. (Lyrics translation above courtesy of Princess of Tea. )

The song has, as they say, “gone viral,” presently being heard around the world, and generating interest even in the U.S. The first time you heard it, you might have thought, “Well, okay, here’s one more K-pop song I don‘t care about but nevertheless will be forced to listen to whenever I go out in public.” And you’d have been was right, of course, but probably none of us expected the popularity to reach out as far as it has in such a short time–and I believe Park Jae-sang (a.k.a., Psy) did not expect it either, even though this is just the sort of thing music groups and entertainment industry leaders have been trying to engineer for a while now.

Why the mass hysteria? I honestly don’t know, but then again, I don’t know why most popular songs become popular, and I think there’s no science to it, no one really knows, which is why such massive popularity often comes about so unexpectedly.

Okay, there’s a bouncy Euro-pop beat and strong male vocals, okay, a hook that pops out at the listener unexpectedly, and turns out to be hard to resist. The melody fits right in with what a lot of other local artists are doing, derivations of American hip hop and gangsta rap, but combined with vocal delivery that (to me, at least) harkens back to an older style of Korean popular music called teuroteu, which is still sometimes heard playing in taxi cabs and cabarets frequented by Koreans of mature years. It’s an unexpected combination of sources, some of which are not immediately recognizable.

And yet the song has spawned tribute-imitations from Singapore, Taiwan, the U.S. and elsewhere, and to explain that I think we’ll have to look at the video–and let’s note that a lot of this refers to aspects of Korean life that might be less than familiar to those who are unfamiliar with this place.

You’ve got a guy, plainly over 30, wearing really goofy-looking suits, not all that good shape, who is clowning around in a scattered selection of typical Korean backgrounds, supposed scenes of posh and glamor, from which the rug gets pulled out almost immediately: first, he’s kicking back and catching some rays, but when the camera pulls back, we see that his beach chair is planted in a children’s playground, where a kindergarten kid starts busting some moves and shows him how hip hop freestyle ought to be done; next, he’s in a public bath, a mokyotang, not a tony high-end spa, where he’s nodding off with his head on a tattooed gangster’s shoulder; he’s belting out his lyrics on a microphone while taking charge of the aisle of a nori-bang tour bus full of middle-aged women on vacation; later, we’ll see him striding aggressively toward the camera through a stable full of horses and we eventually do see him sitting atop a horse –but it’s a wooden one, on a merry-go round, which is really the only place you are likely to find a horse in Gangnam. Along the way other K-pop stars appear in cameos, which seems to be quite common over here, and one of them becomes his love interest (they meet on a subway train, not a posh cafe or night club) and from there the video becomes an over-the-top Bollywood-style dance production.

And there is that dance, yes, a new dance, a kinetic meme, not hard to learn, so easily replicated, the “horse dance,” which Psy teaches throughout the video. Apparently the lessons have been internalized in unexpected places: a Youtube video shows a couple of American football players incorporating some of the moves into a victory dance after making a touchdown. Psy almost never rests, by the way, and the only time his feet aren’t moving (though his hands are still waving) is during a brief shot where he’s expounding to the camera from below, said camera then panning back again to show he’s sitting on a toilet with his pants down.

It’s slapstick, sight gags, and odd situations–in other words, pretty much what passes for comedy in Korea at this time. It’s funny enough, sure, but to someone not familiar with the tropes of Korean life, it will look simply outlandish, weird, outrageously bizarre and mostly inexplicable.

And that might partly explain the appeal we are seeing from outside of Korea.

What Gangnam Is

It’s a place, and the name just means “south of the river” in Korean. I lived there for a while when I first came to this country, and it didn’t take more than a week or so to understand that whatever that place is, it sure ain’t Korea. There are some who believe it’s the best part of the ROK, but there are others who think it represents everything that’s wrong with this country.

It is just one of several administrative districts, often lumped together in conversation with its immediate neighbors, Banpo, Seocho and Songpa. It’s an area of Seoul that many consider to be the most important part of the most important city in South Korea.

It’s where the big money goes, where the famous people are, and if you are Korean, and if you have any ambition at all, it’s probably where you want to be, though that has been changing somewhat since I first wrote those words elsewhere a couple of years ago. All the important businesses and retail outlets, both foreign and domestic, have some kind of presence there. They must, and they do.

If you want to buy a Ferrari, you’ll probably go there do it, and same for a BMW or a Jaguar. Ditto for cosmetic surgery clinics, the latest European fashion designs, and tanning salons–and that last one is a little odd, considering that the Asian ideal of beauty is pale, alabaster skin. (See: Kim Yuna.) A friend once lived in this part of city, and when I’d come out to visit, his mock-serious query was, “Now, Bob, did you wipe your feet before you came to Gangnam?” In truth, I’ve often thought I should at least be wearing a tie whenever I got off the train there.

Espresso coffee shops there sometimes have valet parking – yes, that’s what I said. But across the street from that, people are unloading rice in big sacks, and cleaning vegetables out on the sidewalk, just like you’d see in any small town or village, or really anywhere in the rest of Seoul. Gangnam is the place where the reality of Korea’s “economic miracle” is made plain–because, you see, most Koreans don’t live like that, though most would like to.

Please be advised: Gangnam is not really Korea. When I lived there, still new to this country, I found it disappointing in its lack of opportunities for culture shock. In fact, it was so remarkably similar to the kinds of places in America that I didn’t enjoy going to that I’d usually get myself across the river in my off-hours, just to see what Asia really looks like. In short, Gangnam is not my style.

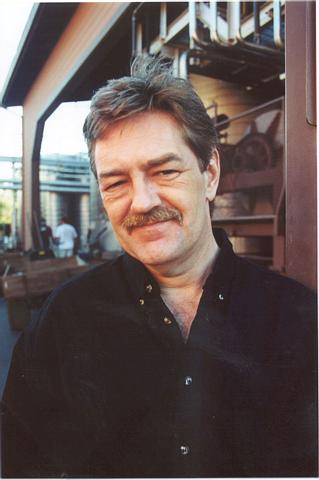

Not Gangnam. (By R.M. Adamson)

In the years that came after, while residing in other areas of the city, I was intrigued to learn what was like to live in a foreign country, which Gangnam is not. It’s a relatively small area in one of the world’s largest mega-cities, yet the real value contained in that small area exceeds the entire combined value of property in this country’s second-largest city, Busan. Enclaves of the super-rich - Beverly Hills in California, St. Moritz in Switzerland, Park Avenue in Manhattan, Monaco, Martha’s Vineyard, wherever they happen to be located across the globe–have much more in common with each other than they do with rest of whatever country they are located in.

I pop over from time to time when a bit of works calls me, or one of my friends sells me on trying out an adventurous new restaurant, but every time I go, I’m left with the thought:

This is not Korea. It’s not even quite real. It is a great, big, bright shining jewel, part of a dream that everyone wants to have. And that very few will ever get to do more than taste, or gaze upon from afar.

Why Gangnam is Bad

At the New York Steak House in Sinsa-dong, around the corner from the trendy fashion street of Garosu-gil, the waiter who brought my lunch spoke to me with such perfect English that I was tempted to demand an explanation about just what the hell he’s doing carrying food to people to earn his right to breathe in this country when so many companies are hiring and promoting people based on their English language skills. Perhaps he just doesn’t like spending all his days cooped up in an office. If so, I sympathize since that’s why I became a teacher.

The bowl of “Steak and Rice” that arrived, ordered from a menu entirely in my native tongue, might as well have been called Sirloin Bibimbab, except there was no sign of gochu jjang (red pepper paste) and the egg on top was poached, not fried. The only thing close to kimchi was cabbage slices, lightly pickled but unfermented. No kimchi? What country is this? I already told you, kid. It isn’t Korea, it’s Gangnam.

I’d had a job interview that morning a short walk from there. The position would be at a public school not far from my own neighborhood, but both I and the school’s teaching staff made the trek across the river to meet in the office of a hiring company on the 7th floor of a tall building. That’s how we all know we are serious about whatever it is we are up to: we arrange to meet each other the first time through a third party – in Gangnam, of course.

By R.M. Adamson

During the interview they offered me water. It came in a paper cup. Yeah, a paper cup. In Gangnam. This did not bode well. A paper cup, in Gangnam? I made it into a joke to tell my friends. I wasn’t surprised when I didn’t get called back, and apparently I was not going to get to see the actual place of employment until I had been given an offer. It didn’t occur to anyone that I was also interviewing them to see if I’d want to work there. It’s part of the sense that one should feel some kind of awe and importance from simply being in that part of town.

That was two years ago. A year later, I took a job as a part-time substitute teacher at a school not far from Gangnam Station, a kindergarten and elementary after-school institute, and after a few weeks they offered me a full-time contract at slightly more than I would have asked for. Good money, in other words, and there was no reason to turn it down because by then I already knew the school and the other staff. I left after three months for several reasons, but I had noticed something in the meantime, that children of great wealth, even of kindergarten and elementary school age, can very early on incorporate the idea that the bulk of the world around them exists as servants dedicated to their happiness. (I want to make it clear that I’ve never been treated unfairly in any way by any of the Gangnam concerns I’ve worked for.)

The reality and the dream. (R.M. Adamson)

You might be guessing at where I’m going, that Gangnam is a bad place because it is full of rich people, blahblah, and that money corrupts and vast amounts of it are bound to do so even more, blahblahblah–I’ll admit, it’s some of that, but not only that. Great wealth does not automatically lead to moral decay or arrogance. More often it leads to a sense of separation from the rest of society, and a sense that one is entitled to what has been given, usually by accident in the case of those who were born into it, which is the case today for many Gangnam residents, especially the young, those who come into life without having in any way to struggle at all.

Gangnam was not my first exposure to the super-rich, or those with pretensions that bend people toward it, and my response in such circumstances has often been an attitude of amusement. I’ve never been unaware of the fact that however much I might have worked for what I have in life, I was also given much and helped much by others, and I’ve also known that so many people exist who haven’t been given so much or been helped by others–and so when I’ve come in contact with people who were given vastly more and feel it to be a result of perhaps a genetic superiority … well, there is something ridiculous, something laughable somewhere in that, certainly.

It even seems possible that Mr. Park, Psy, has come up with a similar strategy.

Is Psy a Subversive Satirist?

There has been some interesting speculation that the song and the video present satirical depictions of modern Korean aspirations, and I owe some debt to an article in the Atlantic for piquing my interest enough to give the song and video a second look. The idea presented here is that PSY is tweaking Gangnam’s collective nose at the same time he makes fun of himself. He (or the character he’s created) wants to be this guy, the guy he describes “a man who knows a thing or two,” and thinks that simply asserting that he deserves the good life is enough to make it happen for him. He has both swagger and at least the modicum of swag and that ought to be enough to get him what he wants, and to get him the girl he wants … and yet there he is, singing on a tour bus, riding a carousel, waving his finger at the ceiling with his pants around his ankles in the crapper.

He’s got attitude, all right, but his values and his goals are hollow, shallow and lacking in substance–just like the crass materialism and designer-label carapace of Gangnam itself. His character shouts constantly, “I AM Gangnam Style!” and yet it’s nothing more than a comical pose, one that he himself sees no irony in. Thus, he is a buffoon, weird clothes and idiotic horse dance and all, and by extension, the actual people living in Gangnam and desperately seeking the Gangnam lifestyle, are also unknowing clowns.

Others have said that he embraces his Korean-ness with all those typical location shots in the video, and that this sets himself apart of other K-pop artists who film their music videos in studios and almost sanitize the images of anything that smells remotely like kimchi. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Jeff Yang makes comparisons to Korean performance styles from previous centuries:

PSY belongs to an established genre of entertainers that pop pundits there have dubbed “gwang-dae,” after a caste of performers traditionally attached to royal households.

“Gwang-dae are more clown or jester-like,” says Kang. “They don’t have to be sexy idols to be popular. Their songs are either very humorous, or can sound serious, but with silly lyrics.” (…)

The original gwang-dae were given a certain amount of license to critique the aristocracy, offering up satirical commentary on society through their dance, music and repartee.

This idea supposes a place for Psy in the cultural history of the Han people by showing a precedent in which the jester, standing outside and powerless himself, might speak truth to power by means of sarcastic jokes and parody. I like the idea, but describing that such a tradition existed in the past does not mean that it continues in anything like that form today, when so many other traditions have disappeared or become radically altered through disuse, calamity or the necessities of the modern world. In much the same way, even if we insist that a tradition from feudal times such as this were still active in modern Korea–and perhaps I’m merely unaware of other examples–I think it would also be necessary for Mr. Park to consciously and publicly assume that role of social commentator, and to my knowledge he has not done so.

Rather, to the contrary, every interview or fan piece I’ve read in his regard suggests something else, that he really just wanted to help people have a little fun, and I’m inclined to believe him. In this song, at least, he’s not speaking even one syllable of unwanted truth to actual places of power in this country–the Blue House, the corporate-sponsored media based in Yeouido, the head offices of Samsung andHyundai–but rather he’s painting a caricature of the societal effects of those power structures, and the way people react to them.

Psy has at times been called a yeupki gasu, (roughly, “weird singer”) but that’s a far cry from suggesting he’s engaged in the kind of social criticism that challenges the status quo–for that, you’d have to look at the podcast comedic troup, Naneun Ggomsuda, who have so irked those in the halls of power that one of their number has been serving a year’s prison term under the harsh defamation laws here.

Psy studied music while living in America for several years, and despite the language ability that would allow him, it might be worth noting that he’s neglected to insert any English words at all into his song, except in the bridge: “Hey, sexy lady.” This is in contrast to most other K-pop artists that do so much more and end up with cringingly wrong grammar or usage errors. (Lee Hyori is a repeat offender, it seems.) He did not begin as a consciously-constructed corporate artifact, as nearly every other K-pop group undoubtedly is, and he writes his own songs choreographs his videos–the “invisible horse dance” belongs to him, and him alone–but he has been signed to YG Management for several years now so he is part of K-pop, not standing on the outside laughing.

All this supports the idea that his intended audience was Korean people rather than the outside world. He has said that he wanted to give people some giggles because the weather was so hot this summer and the economy isn’t working so well–on the other hand, it seems to be getting warmer all over the world, and the economy is hurting pretty much everywhere. Koreans aren’t the only ones who need a good laugh.

Is this song in fact social commentary, sarcasm in a directed attack at prevailing social attitudes? I’m not convinced, though I’d like to be.

Gandhi was once asked for his opinion of Western civilization, and he famously replied, “I think it would be a good idea.” I think that applies here as well. It would be a nice thing to see someone at least attempt to demolish the respectability and expose the paltry nature of what so many aspire to in this country–the exclusive night clubs full of women (and sometimes men) enhanced by cosmetic surgery, the foreign cars and the highrise hotels and apartment complexes, the love of things only for the fat nature of the price tag and little more. It would be nice–and it might be even be necessary–for someone to point out that these things are not going to work out for everyone, and probably not even for the people who live there.

No Such Thing

There is no such thing as “Gangnam style.” It’s not a real place.

It is a place you can visit, and true, you can even sleep and collect mail there. Yes, people are born and die there. It is a place constructed of illusion, aspiration, financial speculation–in which the value of a thing is determined not by intrinsic worth but rather by what people think it is worth or might become worth, in other words, human desire and greed.

A Gangnam night club by day. (R.M. Adamson)

In fact, it was a place that didn’t exist until a couple of generations ago, and it was created deliberately. The people who built Gangnam probably thought what they had made would be something the rest of the country would emulate and try to achieve, and to a certain extent that has been the case. It has no history, and the people there work hard every day to make the rest of the country become irrelevant. And, this is very important to note, the values embedded in the concept that underlie Gangnam are not Korean value, but rather are Western ones.

It is the home of money, the financial and political power that comes from money and, as well, the home of those who rule and control the important things that happen here, including of course, those handful of families that comprise the three or four most vital industrial conglomerates, the chaebols, along with the larger handful that ally themselves. And in order to maintain any sense of credibility for such entitlement it’s not only necessary to possess wealth and position but also to display the trappings and accessories that go with it. Thus it spreads, and in a small, somewhat tightly-knit and homogenous society such as we see in Korea, attitudes like this produce the constant struggle to attain places for their children in one of the top three universities, the movement of families whenever possible to areas of the city with greater and greater prestige, the consciousness for many that making the money is not quite so important as to be seen spending it.

Youth and beauty can be bought if you have enough to pay for it, so goes the message, an imported car will get you a pretty girl, and status and influence, one’s place in a pecking-order, are far more important than true friendships among equals and respect that is earned by demonstrated ability, and wisdom displayed through compassion and real knowledge of life are not nearly as important as who you are invited to play screen golf with, or how many of your kids will be admitted to one of the best schools.

It’s all image, completely and totally that–because, by the way, Gangnam-gu in Seoul, South Korea is also home of Guyrong Maeul, one of the oldest and poorest shanty-villages on the peninsula. See also Luc Forsyth’s article in Groove Korea. Gangnam is all about that flash and dazzle, expensive meals paid for on a credit card whose limit gets higher and higher every time you pay it off–in many ways, Gangnam represents the worst of what has been going on in America and Europe for the last couple of centuries, along with the wholesale banishment of anything that is in any way unique about this peninsula.

But that might be changing. Unless they work for one of the three largest conglomerates–whose main corporate headquarters are all in Gangnam, by the way–more and more of my Korean acquaintances are willing to say that they prefer living where they do, and are not trying to find a way to get their families across the river and into a high-priced apartment, the prices of which get driven up by speculation as much as by actual market demand. Some are telling me they want to live in a Korea where everyone has enough in order to be happy, rather than a Korea where everyone strives to have way too much.

Consider last fall’s mayoral election, a very close race between a liberal and progressive candidate against a fiscally conservative member of the ruling party. Although polls and the final vote tallies showed a narrow gap in terms of numbers, the conservative candidate lost, having carried majorities in only her own district, Gangnam, and the that of its immediate neighbor, Songpa. A resident of that southern side of the river, she had been criticized in the weeks prior to the vote for having attended a posh day-spa with a yearly membership fee of a million won. The issues in that election had voters deciding between a free lunch program in the public schools (the progressive candidate) or a public works program to build one more bridge across the Han River to connect the older parts of the city with Gangnam (the conservatives).

(R.M. Adamson)

I’m happy to report that more and more of the Koreans of my own personal acquaintance are coming to see that money and position are only tools we use to attain security for the future and some measure of happiness in the present – that a career they can give love to is better than a job to be detested, and that what they do for a living is secondary to the larger goal of simply living. That might be anecdotal, and it might be inaccurate, but I hope it’s a trend.

Psy’s “Gangnam Style” is a hit right now, and at six weeks running it has had greater longevity than most K-pop songs that get released. It will be forgotten soon, and I can‘t say if the people enjoying it are giving any thought to what Gangnam is all about, or see the song as a device to think about what they see as important in life. I’m not sure I believe that Mr. Park was composing an anthem in revolt against the mindset that is represented in the Gangnam lifestyle, and I suspect not. He will undoubtedly have a fair amount of clout in the local music industry, at least for a while, and it will be interesting to watch what he does with it.

_________________________________________________

R.M. Adamson is a proud auto-coprophage (please, don’t look that up) and parts of this article were yanked kicking and screaming from the pages of his paltry and inconsequential blog post, “Gangnam, and a Paper Cup.” He resides in Mapo, which really is a part of Korea, and he no longer lives or works in Gangnam. Very occasionally, he might be observed making repairs at Bobster’s House.

| Thethreewisemonkeys.com 3WM Social Media    |

|

'Hood News Art Event/PSA Expat Life Featured Fiction/Poetry

From the Scene Korean Life Politics Rant Review Student Writing Travel

Recent comments