by Das Messer

AIRPORT GUY

The sanctity of Travel lies in its tendency to command your respect as you set out to peer voyeuristically into other human lives. Navel-gazing at a time like this is over-indulgent and simply uncouth: There’s a time for raw vulnerability, but this isn’t it. Chin up, shoulders back, deep breath: You’re on your own now, Das. Lock it down.

***

If it weren’t for swooping bats, potent whiffs of over-ripe mangoes or the inescapable gumminess of the air; Cassandra and I might not have noticed we were in Colombo. We spent our first night chronicling our time apart over gin and tonics, getting it out of the way to maximize shelf-space for the rest of the trip. I reached for a recycled analogy to sum up what had been preoccupying me until I rediscovered reason on the flight over.

“You know when you’re about to get on a plane – the intercom PINGs and boarding gates open, passengers all shufflin’ into single file just to wait a little longer? There’s always that one guy sitting in the waiting area who just doesn’t flinch. He’s clearly been here before; he’s figured it out and sees no point in queuing. Once I spy that guy, my curiosity about everyone else just melts away. I only want to know about him; where he’s going, where he’s been, and why – when everybody else is so eager to get in line, why does he remain so unmoved? I mean, it’s completely unilateral: I’m just an onlooker, and his very existence will have a profound impact on me, but not mine on him. I mean, maybe it will – but I’ll probably never know. And that’s actually okay.”

PANAMA STEVE

Thanks to Cassandra I’d enjoyed a comfortable period of respite from my typical neuroticism. Prioritizing logistics, practical realities, and overall enjoyment of travelling with my best friend had been a welcome retreat. On her last night in Sri Lanka, we headed down to the local back-packers beach-bar for sundowners and nostalgia. We’d had some grand adventures on the trip so far: having dinner with a local family in their slum-home, driving through hill country, climbing Sigiriya rock, ogling incredible botany in Kandy, visiting tea plantations and turtle hatcheries, being caught in monsoons almost every day, belly laughing from waking moments to midnight – we were satisfied.

We’d met Panama Steve two days earlier up in Kandy and agreed to rendezvous when our itineraries coincided later on. He’d come to meet us on the beach that night and shared his less-than-impressed experience of Sri Lanka, in comparison to all the other incredible places he’d been.

He was the whole package: tall-dark and handsome, young, successful and whip-smart. Having listened since sunset to his nonchalant and generally disappointed impressions of the world, his allure quickly diminished and Cassandra and I clenched our jaws and swapped stolen eye-rolls as a heady swirl of aggravation grew between us.

“Have you ever been fazed by anything at all!?” I snapped.

He looked at me in disbelief and smirked over the candles:

“Oh, you’re good.”

My chair sank a little further into the sand; I curled my fingers under the edge of the plastic table and glared back, ignited.

“You know, I sort of envy you – not even because of this incredible life you live. I envy how little you feel about it, and how rational you are without even working for it.”

“You’re right, I am hyper-rational. I travel the world to find something that will really move me. It’s not that I don’t recognize that something is beautiful, I’m just more interested in how valuable it is.”

“What gives you sovereign authority over what’s deemed objectively valuable?”

“Well, economically speaking – something is only valuable if it’s rare and difficult to replicate.”

I paused, fascinated.

“Actually, if I’m honest, this breaks my heart a little: I don’t believe that value can be derived from utility alone, or from originality. What about love?”

“Sure, I’ve loved people…but I’m yet to find anyone who could give me anything irreplaceable.”

***

Cassandra left the following morning and I followed Steve up the coast to the eerily desolate town of Hikaduwa. We were followed by a persistent pack of stray dogs that reminded me how little power I had there. Our presence as the only foreign souls in town was magnified by ashy skies; a deserted, polluted beach and string of empty resorts gearing to shut their doors for imminent monsoon season.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about what you said last night; it’s amazing you picked up on all of that having only known me for a few hours. I’m quite interested in your opinion: So, what do you think I should be doing?”

I felt a little guilty that he’d given such sincere credence to my drunken psychoanalysis from the previous night.

“What do I know, man? I’m a 24 year old girl. There’s nothing wrong with what you’re doing, at least you’re actively looking for something to move you. I work very hard to be as rational as you are, and mostly I fail. Cassandra has called me the ‘The Tin Man’ for years. She’d say: ‘you think you’ve got no heart, but you’re the most emotional fucker in the whole of Oz.’”

He laughed, “What, are you one of those girls who becomes incapacitated for weeks after a breakup?”

“Not really, but something like that.. Anyway, what about you? There’s got to be someone who’s stirred you at least a little?”

“There is someone, but I have to be really careful about what moves I make.”

“It’s not all game theory, honey. Trust me.”

We met for breakfast the next morning and said our goodbyes. I set off aimlessly down a gloomy stretch of highway in Hikaduwa. Up until this point, my travel companions had kept me happily extrospective; but they’re gone now, and Panama’s stoicism had shaken my walls leaving me vulnerable to a flash-flood of rumination that I was helpless against.

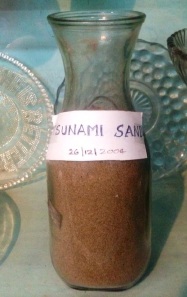

I imagined the wave that was there: The belly of the earth grumbled and purged onto the island with a violent and astringent belch, obliterating everything in its wake. Somewhere parallel to the pock-marked road I found myself on, kept secret by wildly overgrown tropical fauna and freshly chipping tamarind and blue homes, there’s a weary railroad that carried The Queen of the Sea: the train which held 1700 unsuspecting people who trusted her to deliver them safely home to their loved ones; and they were all at once destroyed by the same heartless force.

It’s been a decade since the Tsunami, but everything about this place tells me it remains in a state of incessant recuperation. Kitsch over-development desperately springing up everywhere: beneath lush vegetation and across rattled beaches. Bubbles of rising damp threaten to burst off of buildings whose fresh licks of paint seem nothing but Band-Aid attempts to return this languid town to the lively paradise it once was. All I can do is sympathetically acknowledge gaudy and insipid attempts to actively heal.

I thought about how difficult grief must be in such a blameless travesty. At least in war there’s someone to blame, a recipient for the anger and hatred; someone to pin responsibility to. War is an active engagement, whose aftermath leaves room for reconciliation and forgiveness. Victims of a natural disaster don’t have the luxury of such closure. The ocean has no ideology; no rights or responsibility; no conscience or desires or reasons for anything it does. Harboring bitterness and anger toward it is futile and toxic, but rationalizations come up empty, and the frustration of being a passive recipient of such a violent force of nature will never be more than temporarily soothed.

Alright, that’s enough. Jesus, Das. Get it together. I put my mind on hold long enough to grab my backpack and ride 17km in the opposite direction I’d originally planned, forcing myself to rather look outward; only after sufficiently chiding myself for comparing heartache to the violence of civil war and calamity.

JULIET

I still can’t pinpoint what it is that enamors me about Galle Fort. The grandeur of the rampart walls, the Dutch-Portuguese architecture, the un-furrowed brows of the locals, or a soft scent of wilted bougainvillea breath hanging in the air under a brewing storm.. I ambled through the streets for hours, among people going about their ordinary lives. I was alone for the first time, convinced that the crumbling coral walls and flaking bark of ancient oak trees all had some story to tell me.

I met with Juliet Coombe the following morning and was lucky enough to be the only person on her walking tour. It didn’t take long before I was overwhelmed by the information that tumbled from her lips.

Overlooking the bay she pointed out the area that houses over 1000 shipwrecks; the chain-rings on the walls that held  the slaves at night centuries ago, and the caves that they’d come to call home once liberated. The same caves were inhabited by locals that’d been displaced by the war until as late as 15 years ago.

the slaves at night centuries ago, and the caves that they’d come to call home once liberated. The same caves were inhabited by locals that’d been displaced by the war until as late as 15 years ago.

The tour came to a close at Royal Dutch Café, run by local story-teller Fazal Jiffry, who I’m told cooks an incredible curry and is always up to speed on all current affairs. Juliet mentioned to him that I’d come from Korea and he rattled-off information about a recent train-wreck in Seoul I was abashed to know nothing about.

Juliet ordered a pot of cinnamon tea, explaining that when Sri Lanka when settlers first arrived, tea and cinnamon were valued equivalent to gold, people actually bought their houses with an ounce of either. Today, cinnamon tea is a staple is almost every home on the island.

Fazal brought out the tea together with a large, worn photo-album. Juliet explained that since it’s’ walls were impenetrable; the Fort and its’ 1300 occupants were hardly touched by the Tsunami. Galle city and other villages on the outskirts had been devastated, so the Fort had been temporarily converted into a make-shift hospital. Fazal had gone out to the affected areas and wading through chest-deep waters to photograph the scene, someone had to. I couldn’t tell you exactly what I saw in those photographs, but as I flipped the pages my own walls collapsed as I placed my shaking tea cup onto the table and began to cry.

Juliet is speechless for the first time in two hours.

“Oh god, I’m so sorry. It’s just all so much.”

She sits quietly, respectfully letting me weep for a good few minutes before reaching out to steady my trembling hands.

“Please, don’t apologize” she said firmly. “It’s refreshing to finally meet someone who’s unafraid to be moved by this place.”

She quickly picked up on my shame and embarrassment and started to probe for their source. I tried to be as vague as possible, but I had been rendered so vulnerable at this point that further humiliation seemed impossible. I’d explained how, out of shame, I’d tried to out-rationalize everything I’d been feeling, and that I felt weak having failed to hold it together for even a full day without someone to distract me.

“I even feel guilty for empathizing here, like it’s not my place to come in and be miserable where people are trying to heal. The notion of escaping to and aligning with such a wounded place to gain perspective and spackle my weary heart just seems, well – selfish and menial.”

“No, that’s not right. You shouldn’t be ashamed of feeling anything, Das. You clearly have a big heart and that’s important. A capacity to empathize is what gives you your humanity. It takes a lot of strength and courage to feel as much as you do, and you should really take pride in that.”

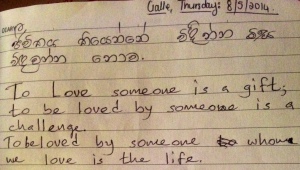

We spoke intimately for a few hours at her husband’s ‘Serendipity Art Café’, exchanging life stories and rich insights on art and love and family. She wrote me a heartfelt and encouraging letter in my notebook before I left. Rushing with appreciation for the kind of encounter I’ll always cherish, I meandered around the Fort some more, allowing everything I’d learnt from her to settle in.

This woman’s seen it all – perhaps she’s right. I’d always viewed emotional hygiene as a luxury reserved for those who’d successfully managed to put food on the table, as if love (like self-actualization, art and armchair philosophical musings) were some sort of delicacy at the height of Maslow’s hierarchy, to be savored by only those who could afford it. I started to wonder if that were really true, perhaps my guilt was actually misplaced and I should attempt to embrace my natural empathetic and amorous tendencies.

NAREN

“Se-ne-ha-sa”, he said, gently releasing the necklace onto my collarbone. “It means…like love, but different…more like sincerity.”

I’d bought the dainty, heart-shaped pendant in spite of the fragility it represented; an act of rebellion against all the shame I’d ever felt for being sincere.

“It suits you”, he says, holding stronger eye contact than I’ve received in a long time. The good kind: strong and confident, but gentle and warm. I recognize his hopes immediately, and simultaneously begin to regret what I’ll inevitably have to tell him.

Naren is a genuine, self-assured, good-looking man who is home from Colombo for vacation. I met him at his cousins’ store in the Fort and we hit it off with general small talk about cricket and travel and Sri Lanka. He was on his way to observe the local Hindu Temples’ Shiva worshipping ceremony – just out of curiosity. He invited me to join his little investigation but I politely declined, instinctively fabricating dinner plans with a non-existent travel partner. He then asks me to accompany him and his friends later on at Pilgrims Lounge on Rampart St., the only place in the Fort that serves alcohol after 9pm.

I arrived early and sat alone at a table watching them play Carom, a strange finger-board/billiard fusion game. I watched him and his friends exchange telling glances, and noticed the tone of questions they asked him in Sinhala. The night rolled on and the glint in his eye grew a little brighter as we spoke and laughed and drank. I decided it would be best to leave sooner rather than later to avoid the wrong impression, but before I go he asked me to lunch the following day and I accepted.

I’d met Juliet in the morning and our conversation had been so consuming that I’d completely forgotten to meet Naren. I wasn’t feeling as guilty about leaving him in the lurch as I was nervous about what might be implied if I suggested I “make it up to him” by going to dinner instead, still – it was the right thing to do, I think.

We agreed to meet at the lighthouse bastion at sunset. About an hour earlier than that, I took a long stroll along the rampart walls to absorb the harmonies emanating from the Mosques in town and admire schools of girls in crisp, white hijab’s giggle quietly as they gracefully navigated muddy footpaths. Sinister birds circled overhead and monitors crawled up the walls with slow, calculated steps. Naren’s approaching silhouette was all that awakened me from passively assimilating everything around me.

“It’s a full moon tonight,” I say, neck bent.

“You are the moon. I will be your sun.”

I admire his quick wit and exhale a light chuckle – thinking: No honey, I’m a god-damned supernova!”

“Alright, hon. Let’s go eat.”

Before we enter the restaurant he pulled me aside and kissed me. Uh-oh. Tread lightly.

“Uhh, Naren, listen…”

“You have a boyfriend?”

“No, but…”

“But there’s someone waiting for you?”

“Well, no. But…”

Slightly discouraged, he pauses for a minute and looks out at the lighthouse behind me.

“You are like a ship, but your captain is misled. I’ll be your lighthouse. But you know,” he continues, “…the lighthouse can’t be moved. I can show you the direction…and you can come to me, and then you can go somewhere else.”

I was stunned – He’s actually serious.

“There are many lighthouses that can show your direction, but you have to stop at a destination. You’ve come into my life, and now you’ll go away – and you’ll leave me sorrowful and lonely.”

THE RETURN

As I journeyed back, I noticed an absence of guilt about how I’d left things with Naren. Perhaps because we’d found ourselves in similar positions, allowing our gaze to rest idly on the static and unmovable. Maybe it was because I’d finally decided not to act disingenuously. Either way, I trusted that he would find the same resolve I had: that a gaze needn’t be acknowledged or returned in order for it to be meaningful.

I spent the ride up to the airport with my head hanging out of the tuk-tuk, ignoring any impulse to analyze or feel or rationalize. I just wanted to see things; observe and admire everything that flickered through my life. I smiled at kids in school uniforms clinging to their parents on scooters; noticed silhouettes of grown men scurry up coconut trees to stock up before nightfall; watched throngs of neon-sari clad women hustling in bazaars; leathery old men play cards at stained plastic tables as bald, orange-robed adolescent boys walked by. Dazzled by the lives whizzing by me under a fading amber light I’d never seen before, not a single ‘Why?’ crossed my mind.

***

Boarding the plane from Narita to Busan reminded me of the state I was in when I left in the first place. I’d been frantically trying to figure out why we love the un-deserving and admire the un-receptive.

Somewhere on this trip I learnt that we’re nurtured by the act itself: loving, being kind, creating things, reading philosophy, travelling, admiring from a distance. There’s nothing altruistic about it. We recognize that we are alone, and rather than relinquishing to emptiness we engage with the world and people outside of us. We do these things because they make us better – and because we can.

Love isn’t some decadent dessert; and it’s not a gluttonous offense to enjoy it. It’s warm, tasty, and available almost everywhere, at whatever price, strength or sweetness we prefer; whenever you’re thirsty for more than hydration alone.

First to board, I settle in comfortably, heartened and fortified. The same stewardess from the day I left is on board, I remembered her kind discretion as she handed me a tissue while I wept. I didn’t expect her to recognize me, but I smiled at her anyway.

“Hi! I remember you. You look like you had a good trip! Can I get you anything?”

“I did, thank you. I’d love a cup of tea, please.”

Recent comments