In what seems to have become an annual rite these days, reports have named South Korea as having the leading suicide rate of all OECD nations. The latest data, taken from 2009, presents shocking numbers to those who haven’t heard them before. A total of 15,413 people died by their own hands in that year, an average of over 42 per day. According to the Ministry of Health and Welfare, suicide has now become the number one cause of death among those aged 10-40, beating out auto accidents, cancer and all other diseases. Among those in their 20′s, the suicide rate was nearly equal to all other deaths combined at a mind boggling 44.6% in 2009.

While the raw numbers always manage to surprise me, unfortunately they aren’t saying anything new and the calls for greater prevention and support with undoubtedly follow as well. The question is, will anything really happen? A look through blogs and news archives shows that the problem has been a part of the social consciousness for at least the past five years.

Suicide in South Korea Case of Too Little, Too Late (OhMyNews Feb. 2007)

S. Korea has top suicide rate among OECD countries: report (The Hankyoreh Sept. 2006)

Reading these and reports from other years, you can see how interchangeable they really are. Unfortunately, the only thing that is changing is the numbers (they are still going up). Additionally, the international media have began to take notice as well, focusing on the angle of high profile suicides among celebrities and as a cautionary social note in the backdrop of Korea’s meteoric rise.

Suicide in South Korea (The Economist July 2010)

South Korea’s Suicide Problem (The Wall Street Journal July 2010)

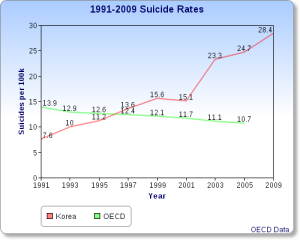

What is perhaps the most troubling point of all is how incredibly recent this trend has began. In only about 20 years, South Korea went from having one of the lowest suicide rates of developed countries (7.9 per 100k in 1990, well below the OECD average of 13.9) to the by far and away highest (the 2009 rate nearly 10 suicides per 100k higher than Japan, the number two nation). So incredible is this increase, that in reporting the statistics for 1990-2006, the OECD had to insert a chart break in a graph expressing a general downward trend in OECD nation suicide rates. That number just seems so patently impossible, 172% increase in 16 years. Also note that the 2006 numbers showed a brief dip in the rate before beginning another upward trend. If we then take into account the 2009 numbers, we have a well over 200% change over two decades.

Undoubtedly, a number of social issues in modern Korea undoubtedly are playing a role in the staggering increases. Common themes include hyper-competitive education and job markets, increased emphasis on social status and appearance, the aforementioned (and constant) celebrity suicides and the break down of traditional support networks. While certainly steps can be taken to mitigate the effects of these phenomena, they will still be facts of modern Korean society and can’t be eliminated completely. Therefor, any solutions based solely around them will be fatally flawed. In my view, the key will be for Korea as a society to revise its view on mental health. The government has attempted to do its part by increasing the number of mental health care facilities available and according to a 2006 World Health organization report, adequate numbers of mental health specialists exist. The problem, then, seems to lie with the use of these resources, integration into general health care and (as mentioned before on this blog) largely negative public opinion towards mental health care. For those without “severe” mental health issues (such as those requiring hospitalization) care and treatment are incredibly limited, clustered only around major urban areas and (if made public) have strong stigmas of personal failure and severe deficiency for those who utilize them. This social stigma, perhaps more than anything else, may be what drives the rates so high, with death seeming to be a better option than living with the assumed shame of seeking help. When I literally look around the Korean landscape with my Western eyes, the complete invisibility of self-service mental health care (psychiatric offices, counseling centers, etc.) is clearly evident and while I feel countries like the US have become too reliant on “chemical care” for mental health, if the other option what we see in Korea, then bring on the pills. I do hope, though, that the future doesn’t lie in either of these extremes. In general, I greatly admire the Korean health care system, especially in how it blends modern Western techniques with Eastern practices and both well supported by the public. If similar systems can be found to treat the mind as well as the body, then perhaps the trends can be tamed and perhaps even reversed. Unquestionably, the first step in any solution will have to take place in the minds of the public. Not just to recognize the problem, as we can see that has already been done, but to accept and seek out the solutions, wherever they might be. Once this has been done, then perhaps the stories can be a bit different in the future.

On a side note, while researching this post and finding some historical sources, I can across this Time magazine piece from 1991.

South Korea: The Tale Behind a Suicide (Richard Hornik, June 1991)

It is a story that I highly recommend reading, looking at one of the well known cases of self-immolation martyrdom among Korean youth at the crucible time between South Korea’s totalitarian past and democratic future. While I personally disagree with suicide ever really being a best solution, I can understand the point that these young people died for something and the nation gained from their sacrifice. Perhaps here, we can see the roots of the social quasi-acceptance of suicide in the modern society. It is a grim irony that the timing of these deaths coincided with the start of the statistics named above, as perhaps we can see the small number of martyrs growing into an avalanche, the death by choice in common, but with purpose and principle lost.

Recent comments