By Peter Ward

Elections have been a passion of mine since I was eight and Tony Blair was coasting to a certain victory of unimaginable scale in the 1997 British General Election. It was a time of great fear in my house—my father and mother foresaw the Britain’s entry into the Euro and the rise of a European super state. This state would envelope our lives and proscribe everything, from our milk bottle sizes to our religion (we would be forcibly converted to Catholicism). As a young boy, I was terrified and transfixed.

Seoul’s Mayoral Election is no different. Well, actually, it is quite different in many regards; I don’t fear my freedom to practice no religion being taken away for one. And the candidates are refreshingly lacking in any noticeable differences save appearance: the candidate of the right is the best looking woman for her age I have ever seen (in Korea), and the candidate for the left looks like a late 19th Century Slavophil Russian author (think Dostoevsky).

The election itself is the result of a typical South Korean political fight. The last mayor, Oh Se-hoon, wanted to mean-test school meals; only poorer high school pupils were to get their daily bread (or should I say rice) free of charge, the rest of the downtrodden would be forced to pay a few thousand won. The left was most concerned about the welfare of richer children and also was most insistent that if the first born of the residents of the Seocho belt were not given their daily ration gratis, it would lead to class struggle (pun intended). Amusingly it was the left arguing this; it led to a plebiscite (or ballot initiative if you must). Oh, a strong rightist, pushed for means-testing, and said he would resign unless he won the ballot. On the day of the event the participation rate was less than the 33% required to validate the ballot and he promptly resigned. This led to our present election.

One wonders how much plebiscites and elections cost. Korean democracy seems to be overly capital intensive and people still don’t seem to care enough to vote. The turnout in the last presidential election was only slightly above 33% in Seoul. Don’t get me wrong, democracy is the best way to sublimate social conflicts into a non-violent and fair process. But it would be nice if people at least pretended to make it seem serious. Most voters worldwide seem to lack the zeal required—I am no exception I suppose.

The candidates in the present election are quite representative of the nature of South Korea’s democracy. Na Kyung Won, the candidate for the Grand National Party (Han-Nara dang), graduate of Seoul National University (Law, doctorate) promises to make major cuts to the deficit whilst concurrently increasing the housing stock and cancelling some of the previous mayor’s most ambitious construction projects (a bridge among other things). Her promises sound good; she also plans a number of expensive improvements to the welfare programs Seoul runs. Her opponent is the candidate from the unified left, Park Won Soon. His promises are similar to hers, he just promises to spend more and concurrently save more.

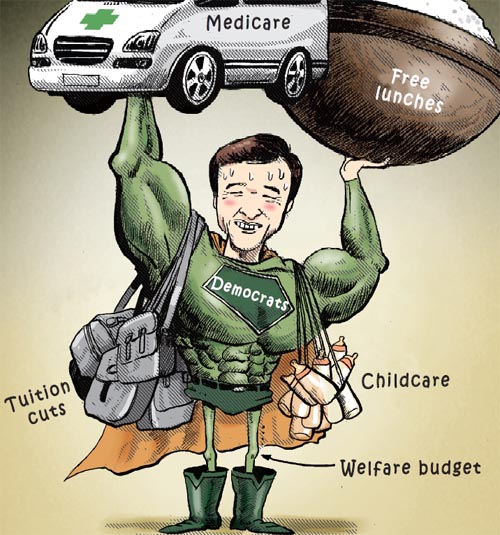

But what are the major similarities between the left and right? There are two major similarities. First, the left and the right are very interested in Welfare populism. This is the buzz word of the Korean political world at present. The mainstream right and the whole of the left are big fans of the idea of spending lots of money on improving the lives of the poor (housing, health care, child care). This is actually very important; think of the people who still live in late 1970s apartments for one, or the people who struggle to pay their medical bills. Also South Korea’s birth rate is one of the lowest in the developed world and the idea of better childcare is very popular with many because it is seen as the panacea to the crisis the nation is facing in manpower. One should remember that South Korea is still an ethno-nationalist place, so maintaining the bloodline is quite important.

Second, both the left and right are making absurd promises—Seoul’s and South Korea’s national debt have been rising for the past 5 years, especially the last three. The world economy is not in good shape and whilst the South Korean economy continues to grow, it is being shaken by high commodity prices, a weak won and economic problems in major trade partners (i.e., the United States and the European Union). Therefore, the promises to simultaneously cut debt and increase spending are completely nonsensical—even if the government of Seoul were to cut spending it would still struggle to plug its deficit.

Where the two parties differ is in the degree to which their promises are absurd. The left, like the British left in the 1960s, does not seem to understand what money is and how one should account for it. The right seems to have a slightly stronger grasp of what money is. Both sides are doing their best to play up to the popular mood with one side being ever so slightly more realistic.

The second major point of conflict is foreign policy. When one usually thinks of mayoral elections, one doesn’t usually think of sea warfare. But the Cheonan incident on March 26 last year has proved to be a sticking point. A little background is probably helpful in this area. The sinking of the Cheonan happened on the watch of conservative president Lee Myung Bak. To sectors of the left, this in and of itself is proof that it was part of a conservative plot to win the June 2 elections (though this, if true, went badly wrong given a landslide result for the liberals). There are large sections of the left that still doubt the official version of events. Forgive me, but when the same kinds of events (i.e., naval battles) happened under progressive President Roh Moo Hyun and Kim Dae Jung’s terms in office, no one doubted who the perpetrators were. The left is used to suspecting the worst of the right as many of them associate it with the military dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s which used bellicose anti-communist rhetoric to justify draconian restrictions on individual freedoms. To many on the left, President Lee is little better than his military predecessors. He is allegedly hell bent on bringing back military rule, through masterly using red terror and alleged superhuman powers to cover up the conspiracy.

The second major point of conflict is foreign policy. When one usually thinks of mayoral elections, one doesn’t usually think of sea warfare. But the Cheonan incident on March 26 last year has proved to be a sticking point. A little background is probably helpful in this area. The sinking of the Cheonan happened on the watch of conservative president Lee Myung Bak. To sectors of the left, this in and of itself is proof that it was part of a conservative plot to win the June 2 elections (though this, if true, went badly wrong given a landslide result for the liberals). There are large sections of the left that still doubt the official version of events. Forgive me, but when the same kinds of events (i.e., naval battles) happened under progressive President Roh Moo Hyun and Kim Dae Jung’s terms in office, no one doubted who the perpetrators were. The left is used to suspecting the worst of the right as many of them associate it with the military dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s which used bellicose anti-communist rhetoric to justify draconian restrictions on individual freedoms. To many on the left, President Lee is little better than his military predecessors. He is allegedly hell bent on bringing back military rule, through masterly using red terror and alleged superhuman powers to cover up the conspiracy.

The point of this is that it was very difficult for Park Won Soon to answer the question thrown at him during a debate by his opponent as to who he thought was behind the Cheonan’s sinking. As the candidate of the united left he would risk alienating his base by saying that he did not at least doubt the official line. But at the same time, such statements do not pay well with the average middle class, independent Seoulite, who probably does not think the man that they put in the Blue House with their vote in 2007 was behind the sinking.

The point is that most Koreans are not partisan but relatively conservative. The electoral victories of the left in the South in the past have never been purely ideological (with the exception of elections in the 1940s). The left is popular only when the right fails. Its rather militantly pro-Pyongyang elements are not much liked by most voters who would be inclined to punish the right from time to time.

Thus Park, after expressing his doubts, was forced to admit (by his opponent), that he thinks it was probably the North but that the “Lee administration provoked the North.” Park is a smart man, a lawyer; he has published many books dealing with welfare issues

and poverty. He has worked for charities dealing with the impoverished members of South Korean society. He is clearly an admirable man, it’s just a pity that the politics of the left in the South are, at times at least, so sickening.

The left has a golden opportunity to win. But they cannot seem to pragmatically throw away their conspiracy theories and their overly dovish approach to Pyongyang. The right is extremely unpopular and they will probably lose the next general election. This is not easy for me to understand—South Korea is of course experiencing economic difficulties because of inflation (and therefore less employment opportunities). But these problems cannot be easily alleviated by politicians, nor are they caused by bad policy, at least not in South Korea (why aren’t the South Koreans allowed to choose the US Treasury secretary?). Nonetheless, the election is very close (with this last poll showing Na ahead). The left needs to learn to show some civility to their opponents. If it does, then it will win this election, the general election and the presidential election. If it doesn’t, then it could be another five years in the wilderness.

(Click here for a full rundown of the campaign pledges).

______________________________________________________ Peter Ward lives and works in Seoul as a student of the Korean language and Korean history. He also has a burning interest in North Korea and North Korean related issues.

Peter Ward lives and works in Seoul as a student of the Korean language and Korean history. He also has a burning interest in North Korea and North Korean related issues.

| Thethreewisemonkeys.com 3WM Social Media    |

|

'Hood News Art Event/PSA Expat Life Featured Fiction/Poetry

From the Scene Korean Life Politics Rant Review Student Writing Travel

Recent comments