The essay below is a reprint of something I wrote for the Lowy Institute a few weeks ago (original here). I got into back-and-forth with Brad Glosserman and Hugh White over Chinese foreign policy intentions. I am still not entirely sold on the idea that China is a full-blown revisionist, like Putin, or worse, Wilhelmine Germany. There are other possible explanations.

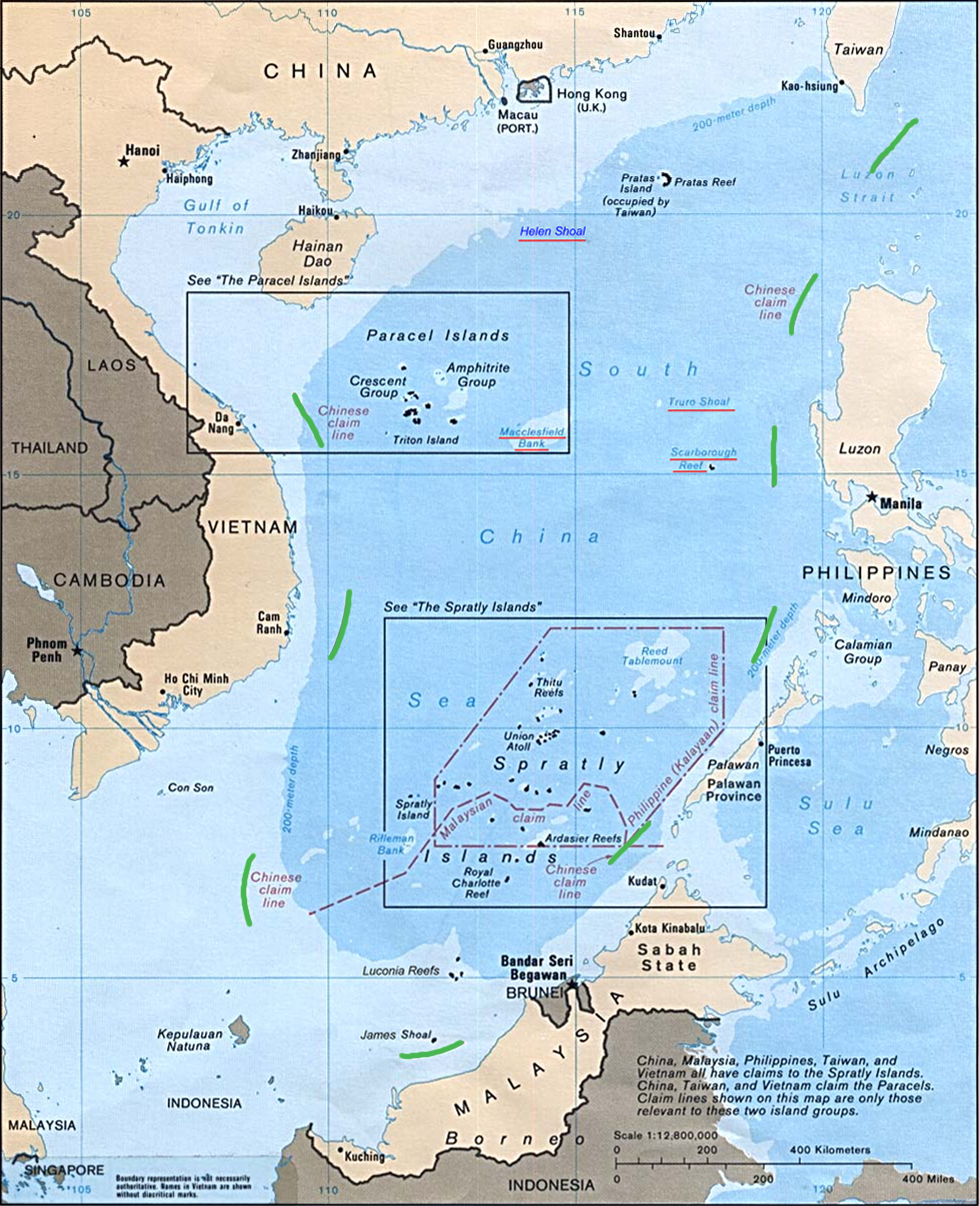

The map to the left is the so-called “Nine Dash Line,” China’s preposterously capacious maritime claim in the South China Sea. I wonder if it’s even worth noting anymore that UNCLOS can’t be possibly be used to justify this. Everyone knows that now, right? The claim is just nationalism, pure and simple.

What’s really struck me though about China’s maritime claims is how Beijing has really ramped up the tension in just a few months. In the last 9 months, China has picked serious fights with Japan (over its ADIZ), the Philippines over Scarborough Shoal, and now Vietnam over that oil rig. That much bullying in such a short period of time, very obviously coincident with Xi Jinping’s ascension, pretty much tells the world that the new Chinese administration is becoming the regional bully we’ve all been fearing for 20 years. This strikes me as unbelievably foolish, as there is a very obvious anti-Chinese containment ring waiting in the wings. A lot of people in the US, Japan, and increasingly Southeast Asia would be happy to see this outcome. My strong sense is that US patience particularly is running out, and that ‘neo-containment’ is around the corner.

So this essay is a last ditch effort to try explain Chinese belligerence as an outcome of Chinese dysfunction. Let’s hope this is right, because if the hawks are right that arguments such as mine are just excuse-making for Chinese belligerence, then I guess we have to contain China. Scary stuff.

“Last week, Brad Glosserman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies made the smart observation that China has recently chosen a surprisingly hard course in its foreign policy. It has lately picked a series of fights with its neighbors which threaten to derail the ‘peaceful rise’ policy which facilitated so much of its earlier growth. Brad finds this bizarre and wonders whether the new Chinese leadership knows what it is doing – or where this will lead: to more clashes and open balancing against China.

Hugh White responded here at Lowy that this behavior is a part of China’s larger plan to slowly push the US out of the Asian region. China has learned from the Soviet Union – instead of confronting the US directly and provoking a big response, the Chinese are looking for small cracks, like the Senkaku Islands or Scarborough Shoal. These pressure points fall below the American radar; America, it is often said, will not go to war over some uninhabited rocks in the western Pacific. But on the other hand, by bullying neighbors over these low stakes and winning, China sets a precedent and reinforces its image as the emerging regional power. This is a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ or ‘creeping normality’ strategy: China is slowly reconfiguring the east Asian board by small moves, none of which is big enough to cause a breach, but which in toto change the status quo in its favor.

If White is correct, then the peaceful rise is indeed over, and east Asia looks likely to conform to realist models that project Wilhelmine Germany onto modern China. The militarized pivot should then continue, the US should indeed to prepare to fight over some ‘uninhabited rocks,’ and containment is likely. Before we go down this frightening road however, there are alternative, domestic explanations for China’s recent behavior, which flow from ‘Hanlon’s razor’: never attribute to conspiracy that which can be just as easily explained by incompetence. In the context of China’s rise, what looks to White like a larger plan to push out the US may be far less organized and coherent – the outcome of a series of domestic factional battles in a new administration rushing to establish itself, control its military, and legitimate itself to a cynical population. We may be seeing more coherence in Chinese foreign policy than is really there.

Alternative explanations would note that China is not governed very well, with a lot of factionalism, military-civilian rivalry, confused lines of the authority between the state and party, widespread corruption, and so on. Such explanations would also capture why China, as Brad has noted, has persisted on this hazardous course despite pushing the neighbors toward America. If White is correct, these Chinese actions should dent the US alliance system and push neighbors to equivocate out of fear. But that is not what appears to be happening. Instead, the neighborhood is drifting toward the US. So why continue, unless foreign policy belligerence serves other, domestic needs?

I can think of two internal explanations, one focused on the new Xi Jinping government’s need for legitimacy, and a second on the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) flagging raison d’etre:

1. Tension with the neighborhood is new premier Xi’s sop to the military and its hawks

I made a similar argument last year about the expansion of the China’s Air Defense Identification Zone. We know that late communist systems factionalize; indeed authoritarian systems generally factionalize as they age. Internal rivalries and power struggles are the inevitable outcome of governance systems without elections. No one knows who enjoys popular support, who is really up or really down. There is no barometer. And when the great leader finally passes, there are strong incentives for all parties to settle on a confused, power struggle-prone oligarchy to avoid the harshness and arbitrariness of the autocracy.

This is where China is today. Post-Mao and post-Deng, no one rules undisputedly and the factional split of the CCP into the ‘Shanghai’ coastal clique of modernizing princelings against retro-Maoist hinterland populists is well-known now. (Xi is of the former group.) And neither can hold power without the support of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Since Tiananmen Square, the party cannot risk alienating the military.

Xi is new. He did not emerge without a fight. He almost certainly made promises to the PLA in order to win the factional power struggle. The PLA is arguably the most hawkish, anti-American faction in the government. Xi is also surmised to have a greater interest in foreign affairs because of his creation of a ‘national security council.’ He needs some manner of legitimating ideology, and ‘more growth’ will not do the trick anymore. It is widely understood now that China’s growth is slowing, and that unrestrained headline growth has generated massive negative environmental and social externalities.

In such a context, ‘naval nationalism’ is not a bad legitimating choice. It keeps the PLA happy and solidifies its support of his premiership. It covers for the inevitable slow-down in growth, and appeals to Xi’s desire for China to play a larger role in world affairs and accrue greater respect.

2. The CCP is effectively obsolete and needs something to forestall multiparty elections, such as nationalism and fights with neighbors

The primary goals of the CCP since the beginning of the republic were to maintain China’s territorial integrity and pull China back to the global esteem it enjoyed before the ‘one hundred years of humiliation.’ The tool to do this was modernization – first (failed) communist, then later capitalist growth. By any reasonable measure, China and the party have done this. China has not spun apart; China is now a middle income state and the world’s second largest GDP. It is now feared globally, if not loved. Its growth trajectory for the future is good. Barring some cataclysm, it seems fair to project several more decades of growth above 5%. Indeed, the only big CCP objective unfilled is unification with Taiwan.

Ironically then the CCP has succeeded to the point where it is longer necessary, specifically to the point where single-party rule for developmental purposes can no longer be justified. China is not really a poor country anymore. The ‘Asian developmentalist’ argument that democracy obstructs growth no longer holds. China is either now, or will shortly, be ready for democracy – its citizens are now educated and wealthy enough that paternalist arguments for party guidance no longer make sense (if they ever did).

But single-party states rarely just give up. And the CCP, while developing China, has also abused it. An embarrassing truth-and-reconciliation process and jail-time awaited the old regime in South Africa; one could imagine the same and more in China. So if they party lacks its old economic and prestige arguments for one-party rule, then how about nationalism? Patriotic education has been the de facto national ideology since communism collapsed with the Cold War’s end and Tiananmen. Xi’s maritime nationalism fits this well. Better tension than transition.

China’s bullying of its neighbors is worrisome. And White may be right that it is a part of a larger Chinese regional strategy to push the US out. But communist states are often badly factionalized actors. Indeed stalinist political concentration, without elections, encourages it. There may be internal reasons explaining recent Chinese belligerence.”

Filed under: Asia, China, Foreign Policy, International Relations Theory

Assistant Professor Department of Political Science & Diplomacy Pusan National University @Robert_E_Kelly |

|

Recent comments