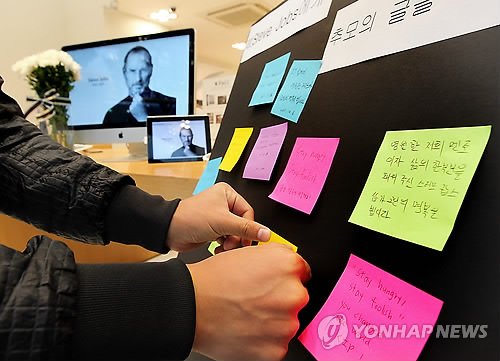

With the death of Steve Jobs last week came an incredible outpouring of support and remembrance from around the world. From my perspective, a surprising amount of this came from South Korea, a place where the man’s products were late to the game and recently have had an increasingly contentious relationship with Korea’s flagship company. I can understand this, however, as even though I’ve never been an Apple person, I can recognize Jobs as a true innovator and the driving force behind game-changing products that have helped define both modern markets and our modern lives. In addition to honoring and memorializing the departed, many of the words spoken and written have had a decidedly introspective tone:

With the death of Steve Jobs last week came an incredible outpouring of support and remembrance from around the world. From my perspective, a surprising amount of this came from South Korea, a place where the man’s products were late to the game and recently have had an increasingly contentious relationship with Korea’s flagship company. I can understand this, however, as even though I’ve never been an Apple person, I can recognize Jobs as a true innovator and the driving force behind game-changing products that have helped define both modern markets and our modern lives. In addition to honoring and memorializing the departed, many of the words spoken and written have had a decidedly introspective tone:

Can Korea Nurture its own Steve Jobs? (Chosun Ilbo Editorial 10/8)

Is Chris Bangle Samsung’s Steve Jobs? (WSJ Korea Real Time 10/7)

‘Creative Korea’ in the future (Korea Herald 10/6, effect of the news on a design conference)

‘Innovation’ had been a key word amongst Korean businesses for a while now, but is reaching fevered pitch these days. The common meme being that Korea needs to foster creative people and organizations to remain relevant in the future. While this theme is certainly not unique in international business, the notable rigid Korean organizational structure makes the comparisons particularly stark here. In my business English classes, it is a frequent point of discussion as “how” Korean companies can make this transition. Most, if not all, of the classes are able to recite off the usual business buzz phrases considered solutions, such as going “outside the box”, having “horizontal integration”, etc. However, when I ask for detail and explanation into these ideas the room tends to go silent. It seems that while the buzz has entrenched itself here, the processes (and problems of integrating these ‘Western’ thoughts into ‘Eastern’ organizations) seem out of reach. While I can’t claim to have the perfect solutions, it’s still important to ask the questions and start the conversation. Namely, how can Korea start the process of nurturing innovative organizations? Also, and perhaps more importantly, is doing so really necessary (or advisable) for Korean businesses?

Beginning at the beginning

First and foremost, organizations are made of people and people tend to be a reflection of the culture and society they grew in. A primary reason for why innovation seems so far out of reach for Korean organizations could be because the traits necessary for it (i.e. creativity, free-thought, experimentation) aren’t strongly developed in the young. To visualize this, I simply look to the education system (note: my personal experiences working within the Korean public education system leaves me with a tendency to rant on the subject, so I’ll try to control that). While there is plenty to like about education here, mostly the work ethic of its students, without question the unforgiving, test-focused measurements impedes growth in more subjective areas. This is not to say there are no creative, innovative Korean people, as there most certainly are, but rather they were created more in spite of the culture than with its support and many cite outside influences as key to their development.

A common attribute of those considered ‘great minds’ such as jobs (or historical figures like Einstein and Edison), is that they failed, a lot. Their path to success tended to be littered with false starts, bad ideas and poor decisions. For every light bulb there were plenty of kenetophones, or in modern terms, for every iPadthere were plenty of NeXTcubes.

I have not failed, I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work. Thomas Edison.

In the West, stories of monumental failure leading to ultimate success are common. They are told to children to encourage the “get back on the horse” mentality that is common to the culture. This stands in contrast to what exists in Korea, something cultural anthropologists call a “shame society”. In short, such cultures use shame and the threat of being ostracized as a form of social control. While the real existence of this in Eastern cultures is argued, there certainly are plenty of evidence to suggest its existence in Korea (such as the high suicide rate discussed before). As to how such a societal structure affects business innovation, I personally can see two major obstacles. First, shame or “saving face” adds additional costs to failure and therefor encourages playing it safe and not taking risks. Second, by placing such high value on belonging and acceptance, standing out (especially in non-academic ways) is a scary prospect, as even elevation in status separates you from the whole.

To recap far too many words, it’s probably suffice just to say to become ‘innovative’, Korea (as a society) would require great amounts of cultural change going far beyond the board room, but into the classroom and the home. I’m sorry for you readers who read through everything else just to get to this point, especially because it’s likely not the most important question. As stated way back at the beginning, that question is this really necessary (or advisable) for Korean businesses?

Focus on your strengths, not your weaknesses

To give credit where its due, my inspiration for this post began with a discussion over on Korea Business Central, asking the question if Korea can design a brand that is “distinctly Korean”, (an extension of a Korea Herald interview with brand consultant Martin Lindstrum). Over there, I made the argument that Korea’s recent history and tremendous economic growth is strongly tied to its decades of authoritarian rule. The powers of this time pushed growth and quantity above all else, making fast and cheap the names of the game. While this time (for the most part) has passed thoughts and images still remain (anybody want a 1986 Hyundai Excel?).

While some of these ideas are no longer applicable, many have simply evolved with Korean society, such as it being better to copy rather than create. When I say “copy”, I don’t wish to compare Korea to the Chinese firm manufacturing $100 jPads, but rather note that, especially in recent times, their strength does not lie in taking the giant leaps, but rather in the little steps between. Put frankly, if all companies were innovators, we’d have a ton of fancy new products (that don’t quite work properly). While it’s commendable to be on the cutting edge, taking and improving on the ideas of others can be a very good recipe for success. While my Western perspective initially lead me to argue that Korea companies need to be more innovative and begin the cultural changes necessary, further discussion and reflection makes me realize that it’s not the only way. For an example, let’s look at K-Pop music.

While a lot of the national hype about its growth is just hype, it is very true that there is an emerging international interest and appeal far beyond the size of the country producing it. This interest likely isn’t due to the creativity or uniqueness of the product (as really, no pop music stone is left unturned in the industry, including disco), but rather that it takes what has been done before and presents it in a highly polished, easily digestible package for the masses. The boys and girls on stage are highly trained, hard working and incredibly talented, not in the sense of writing words and making music, but instead at making something the masses want to consume. More than music, K-pop is a product, an increasingly successful one, that proves it doesn’t have to be original if it good and easily accessible. Really, in the end, Korean companies can continue to follow this model, grow and continue to be successful, as it fits within the current structures of society, ones that would be very difficult, if not impossible, to change. Perhaps the “Korean Steve Jobs” will come, but they undoubtedly will be, and probably should be, the exception rather than the rule. So, at least for today, I have to leave it with the belief that for Korean business to keep moving forward, they’re best left following, but just doing it better than those in the lead.

While a lot of the national hype about its growth is just hype, it is very true that there is an emerging international interest and appeal far beyond the size of the country producing it. This interest likely isn’t due to the creativity or uniqueness of the product (as really, no pop music stone is left unturned in the industry, including disco), but rather that it takes what has been done before and presents it in a highly polished, easily digestible package for the masses. The boys and girls on stage are highly trained, hard working and incredibly talented, not in the sense of writing words and making music, but instead at making something the masses want to consume. More than music, K-pop is a product, an increasingly successful one, that proves it doesn’t have to be original if it good and easily accessible. Really, in the end, Korean companies can continue to follow this model, grow and continue to be successful, as it fits within the current structures of society, ones that would be very difficult, if not impossible, to change. Perhaps the “Korean Steve Jobs” will come, but they undoubtedly will be, and probably should be, the exception rather than the rule. So, at least for today, I have to leave it with the belief that for Korean business to keep moving forward, they’re best left following, but just doing it better than those in the lead.

Recent comments